Evansville Veterinarians – a History of Service

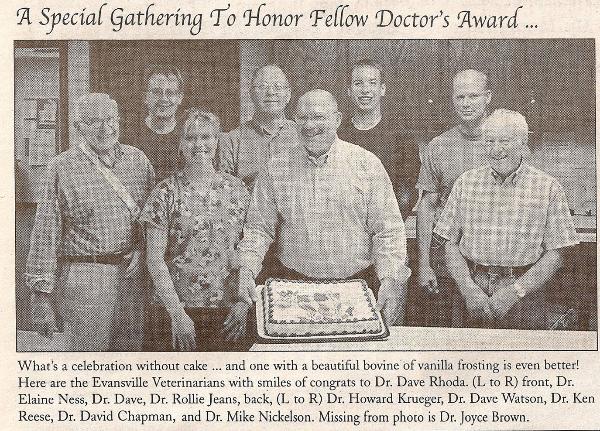

Written and Researched by Ruth Ann Montgomery

Evansville’s Veterinary Service follows a long tradition of care for animals. In January 1866, a veterinarian’s advertisement appeared in the first

issue of the Evansville Citizen, the forerunner to Evansville Review.

The early Evansville veterinarians confined their practice to the treatment of horses. The horse was a very important to the economy of Evansville

and the surrounding agricultural area in the 1800s. Most farmers used horses to work their fields, haul goods to market, and transport themselves

and their families.

Evansville home owners who could afford to keep horses, built their own horse barns. Those who did not own horses and carriages relied on the

local livery stables for transportation. Livery stables offered stage coach and carriage transportation for people and goods within the village of

Evansville and to other communities.

Dr. W. Beach was the first veterinarian to advertise his services in Evansville. Beach owned a livery stable on North Madison Street, near the

Spencer Hotel. The hotel was located on the northwest corner of Main and Madison. He advertised that he was “ready to attend to sick and

disabled horses, and all matters pertaining to Veterinary practice.” Dr. Beach did not elaborate on his qualifications for treating animals, but he

did demand that customers pay in cash.

In the 1800s, many veterinarians were self-taught or received training as apprentices with graduate veterinarians. Some medical colleges

included courses in veterinary science. Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and well known physician, offered

classes to his students in healing animals as well as humans.

The first veterinary school in the eastern United States was established as New York College of Veterinary Surgeons, organized in 1857 at New

York University. There were no veterinary colleges in the Midwest until the Veterinary Medical School was started at Iowa State University in

1879.

Evansville’s first veterinarian, Dr. Beach, moved on without any fanfare and the second veterinarian, known to have practiced in Evansville, Dr.

Thomas E. Lucas, began advertising in 1868.

Thomas E. Lucas was born in Radnorshire, Wales in 1838. He began his practice in Evansville in 1868. He was Evansville’s veterinarian for over

20 years.

Dr. Lucas advertised himself as a Veterinary Surgeon and Practitioner, and a “regular graduate” of the Royal Veterinary College of London.

According to his biography, he graduated from the Royal Veterinary College in 1857. He came to the United States and practiced at Paris,

Kenosha County, Wisconsin before coming to Evansville.

In June 1868, Dr. Lucas opened a drug store on the north side of East Main Street, with George W. Palmer. The store carried medicines for

people and animals and also a stock of groceries.

Dr. Lucas told the Evansville Review reporter than he was capable of helping people, or animals. The reporter described Lucas as a “regular

practitioner and surgeon,” in addition to his veterinary medical skills. “He comes to this place with the best recommendations of a gentleman for

practical skill and ability in his chosen profession.”

For those who could not afford the services of a veterinarian, the local drug stores carried over-the-counter remedies, including Sheridan’s

Cavalry Condition Powders. The advertisement for the powder promised relief for animals afflicted with “loss of appetite, rough of the hair,

stoppage of bowels or water, thick water, coughs and colds, swelling of the glands, worms, horse ail, thick wind and heaves.”

The winter of 1872-73 was especially hard on the horse population in the United States. There was an epidemic was known as the Epizooty. The

disease was first reported in Toronto, Canada and quickly spread into the United States from Buffalo, Rochester, Troy, Albany and down the

Hudson River to New York City. New York newspapers reported the devastating effects of the disease in October 1872.

The rapid spread of the disease was alarming. Within a 24 hour period, 1,000 horses in one New York livery stable showed signs of the illness.

One report estimated that there were 15,000 cases in the city.

By December, the “Epizootic” had spread from New York to St. Louis. Newspapers throughout the East and Midwest carried recommendations

from veterinarians.

A New York veterinarian, Dr. Alexandre Liautard, described the disease as influenza. The symptoms were inflammation of the air passages, mild

laryngitis, congestion of the lungs, loss of appetite, cough, discharge at the nose and eyes, a weak pulse, and weakness of the circulatory

apparatus, high temperature, and yellow color of the mucous membranes. Dr. Liautard claimed that any well-educated veterinarian could

diagnose the disease and, if treated when symptoms began, could be cured.

Dr. Liautard warned against “blood letting, purgatives, arterial sedatives, and setons” that would only endanger the horse. He recommended

acodine and cough mixtures for the laryngitis; liniment and mustard applications, and carbonate of ammonia mixed with camphor.

Dr. Bowlery, the Veterinarian Surgeon of Cincinnati, recommended Allen’s Lung Balsam, three times a day and Davis’ Pain Killer as a liniment.

Both were readily available from drug stores.

Within weeks, the disease spread to Wisconsin and many Evansville area farmers and liverymen reported their horses were sick.

The first evidence of the disease was found in Evansville within three weeks of the report of the outbreak in New York City. Although the Review

seldom used headlines, the spread of the disease to Evansville, was cause for large print. “The Epizootic” was first reported in Evansville in the

November 27, 1872 issue of the Review.

The horses in the Evansville livery stables of Martin Case and Ray Gillman were sick and unable to work. Gillman had 13 horses down, but none

died. Case’s livery was in a similar condition.

W. C. Clark’s stage coach service from Evansville to Union, Cooksville, Dunkirk and Stoughton was halted for a few days. The stage lines also

carried the mail. For a short time during the epidemic, the mail was carried by private parties, because the regular stages could not run.

The Review reported more than 100 Evansville horses were sick. The epidemic brought business to a halt. No wood was brought into town from

the countryside. Many Evansville residents relied on the farmers for eggs, butter, and other produce. One farmer, who still owned a team of oxen,

resorted to using them to haul goods to Evansville.

The epidemic spread into the countryside, to Union and Cooksville. Nearly every farmer reported that horses were sick. Horse owners were

warned to use their horses carefully, keep them warm, and feed the animals cautiously.

Cooksville’s correspondent to the Janesville Gazette reported, “The epizooty is here, but in a mild form, and in most cases nothing but a cough.

The poor equines are sick. We are ready to give ‘our kingdom for a horse’.” In December 1872, the most frequent question in Cooksville was,

“Are your horses sick?”

Similar incidents were reported as the disease continued to spread. A Gazette reporter for Rock County’s Bradford area said: “A few horses have

died the past week in our town of the epizooty.” A mail carrier from Darien to Janesville could not deliver mail because there was no horse that was

able to make the trip.

After the Epizooty disappeared from the Evansville area, it continued its path westward. In January 1873, Evansville’s young artist, Theodore

Robinson, was visiting in Denver, Colorado and reported that the horse disease had reached Denver. “Street cars are stopped, the stables are

full of barking nags, some of the busses and transfer wagons do not run while the express business suffers. One express wagon was hauled by

four men, while another, a sober cow was harnessed with a bit, bridle and harness all complete.”

Work horses and race horses succumbed to the disease. There was even some concern that the disease might spread to humans.

Whatever Dr. Lucas did to stop or relieve the suffering of horses in Evansville went unreported, although he continued his veterinary practice in

Evansville. His personal life was not an easy one. His first wife, Sylvia, died in 1874, at the age of 36 years, leaving him with four children. He

remarried a short time later and his second wife died in February 1876.

Shortly after the death of his second wife, in 1876, Dr. Lucas sold his store on Main Street to Dr. Charles Smith. He married a third time to Ella

Murray in September 1877.

Lucas also had to contend with others who wanted to enter the veterinary field in Evansville. Occasionally a competing veterinarian would

advertise services in the Evansville Review. J. W. Francis advertised briefly in the December 1874 Evansville newspaper. Francis set up his

practice at the blacksmith shop of Stephen Baker. His ad read: “NOTICE, ANY PERSON, having horses with Spavins, Ring Bores, Splints,

Sweeny, Curb, Pole evil, Heaves, Glanders, will do well to call on the undersigned at Baker’s blacksmith shop and have them cured. J. W.

Francis. Evansville, Dec. 2, 1874.” It was a short-lived practice and within a few weeks, the advertising ceased.

Dr. Lucas continued his veterinary practice in Evansville. Within a short while he remarried.

The experience that Thomas E. Lucas had gained as a veterinarian, gave him the idea to write a book that would help the horse and cattle owner

when they could not afford the services of a veterinarian. The title of the book reveals the increasing importance of the dairy cow in the operation

of the farms in the Evansville area. Dr. Lucas had added cows to his veterinary practice.

In September 1879 Dr. Thomas E. Lucas announced that he was publishing the book, “A Practical Treatise on the Most Obvious Diseases of

Horses and Cattle.” The book contained recipes that Lucas had used in his treatment of sick animals. One man, who had used the medicine

prescribed in the book, said that he would give ten dollars, just for one of the recipes.

One recipe was for Acute Garget or Acute Mastitis treatment for cows read as follows: “Epsom Salts, 1 lb; 1 oz of Garget Root Powder and 25

drops of Tinc Aconite. Mix in three pints of water and drench the cow and rub with liniment No. 1, three times daily where the parts point and

contain fluid or pus; open deeply at the lowest point, that the pus may escape without forcing.”

The two roots used in the medicines were commonly used by physicians and veterinarians. Garet Root, also called poke root, was a common

ingredient in remedies for gastric ulcers, sore throats, diphtheria, and skin irritations.

Aconite root was used in the treatment of various illnesses. A powdered form of the root was mixed with other ingredients, depending on the

treatment. A mixture of aconite and alcohol (tincture or tinc) could be used to cure laryngitis. When mixed as an ointment, the aconite mixture

numbed the skin, producing relief from irritations, rheumatism, or neuralgias.

Perhaps Dr. Lucas was anticipating great success with his new book. A month before the “Practical Treatise” was published Dr. Lucas reported

that he was going to stop the practice of veterinary medicine.

In November 1879, his third wife, Ella died and Dr. Lucas resumed his veterinary practice.

Dr. Thomas E. Lucas sold his drug store to Dr. Charles E. Smith in 1876. Smith continued the drug store business and had his office in the

second story of the building (at 5 West Main.)

Although Lucas listed Veterinary Surgeon as his profession in Evansville’s 1880 Federal Census, the veterinary business was seldom Lucas’ sole

occupation. In June 1881, he married his third wife, the “widow Hynes” and they rented a hotel, the Wadsworth house, also known as the

Evansville House. The business was operated as a boarding house, for those who only wanted someone to cook meals, and a hotel for those who

needed a room. (on the site of “The Station” at the corner of East Main and Union Streets.)

There was no competition for Lucas in his Evansville veterinary practice. Occasionally the local newspapers advertised veterinarians from distant

cities who offered mail-order self-help books or medicine. The Review offered J. B. Kendall’s book on the “Treatise on the Horses and His

Disease” as a premium with a subscription to the newspaper. Kendall also advertised Kendall’s Spavin Cure in the Review. According to the ads

the “Cure” was good for humans as well as horses. The advertisements promised Kendall’s medicine could cure lameness in horses and

rheumatism in people.

The hotel business was a short-lived venture for Dr. Lucas and his new wife. In less than a year, they turned the Evansville House, also known as

the Farmer’s Hotel, over to their daughter, Flora, and son-in-law Charles Winship. Agnes Lucas continued to help the Winships with the hotel

business.

Charles Winship was also a licensed veterinarian. However, Winship usually supported his family by operating a livery and side businesses

related to the livery business. Notices in the local newspapers said that he was also engaged in ice cutting, excavation for foundations and

basements, and the draying business.

Another venture for Thomas Lucas was teaching the art of calligraphy and penmanship. On January 19th, 1882, Lucas offered his first class in

penmanship and the Review gave him an excellent recommendation: “Mr. Lucas is a good penman, and teaches wholly by the practical method,

so when a scholar has completed a course he knows something else than the bare theory of penmanship.”

By October 1882, Dr. Lucas, no longer had a permanent location for his veterinary service and advertised in the Review, “leave orders at the

Commercial House.” He promised to “attend all calls in city and country.” Lucas was reported to be very busy due to his wide field of practice.

In the November 24, 1888 issue of the Tribune was an announcement of a new veterinarian. Dr. H. W. Higday and his sons opened a business.

The Evansville Tribune editor, Caleb Libby, said, Dr. Higday, "comes to us very highly recommended, in fact Mr. Higday has been in the horse

business with our brother Harrison in Illinois."

About this same time Dr. Lucas left Evansville and moved to Paris, Kenosha County, Wisconsin, his former home. He remained there for about

two years.

Higley rented a barn on the north side of the first block of West Main Street belonging to Hiram Spencer. He and his sons, H. S. Higley and S. M

Higley announced that they would sell, train and stable race horses.

“Calls in the country promptly attended to; chronic sore feet and veterinary dentistry a speciality,” Dr. Higley announced in the November 20, 1888

issue of the Evansville Review.

Higley had served as a veterinarian in Illinois and in Monroe, Wisconsin before coming to Evansville. He helped organize and manage a race track

on the south side of Evansville, first known as the McEwen race track and later part of the Rock County fairgrounds in Evansville. He also owned,

trained and race his own horses.

Dr. Lucas returned to Evansville in the spring of 1890 and continued his practice. On December 20, 1890, Lucas suffered an apparent heart

attack in his home and died at the age of 52. His obituary said, “The Doctor had been about as usual attending his veterinary business and was,

apparently, in his usual health and spirits, and such a sudden exit startled everybody.” His funeral was held at the Methodist Church and he was

buried at Maple Hill Cemetery.

One man tried to establish a practice, but did not find enough business to make his stay worthwhile. In the spring of 1892, C. S. McKenna came to

Evansville from Chicago. He advertised himself as a graduate of a veterinary college. McKenna either did not name the school, or the newspaper

reporter who announced his entry into the Evansville business community did not add it to the information in the announcement of his arrival.

McKenna never established a permanent office and used the Central House hotel as his residence and office. Shortly after McKenna arrived, he

told a Review reporter that he already had “several cases in which he is attending to with excellent results.”

The reporter observed that McKenna was “not a blow hard but offers his services to the public and hopes to acquire business by his skill in the

profession.” McKenna apparently liked the community and said he planned to make Evansville his permanent home. He wanted to open an

“equine infirmary.” McKenna’s plans did not work out and in September 23, 1892, he announced to the local newspapers that he and his wife

were moving back east. He had hopes of finding a more lucrative practice.

In March 1893, a new veterinarian arrived in Evansville. Dr. Charles S. Ware, was born in Newark-on-the Trent, in Nottinghamshire, England. He

attended Rudlow College in Bath, England and then took additional training in veterinary science.

Ware was an 1892 graduate of the Royal Veterinary College of London, came to the United States from England with his wife, Agnes Bedford

Bazley Ware. Agnes’ brother, Dr. Bedford, was a veterinarian in Janesville.

Their son, Cecil and a niece, Nina, and two nephews, Ernest and Victor Bazley accompanied them from England. A daughter, Constance, was

born in Wisconsin in June 1893, shortly after the family arrived in Evansville.

Dr. Ware’s association with Evansville lasted for nearly 50 years. The Review welcomed the new veterinarian. “Understand that Mr. Chas. S.

Ware, our veterinary doctor, is working up a good practice. He is a man highly skilled in his profession and is using his best endeavors to work up

a desirable practice in this community.”

Another local newspaper, The Enterprise, also welcomed the Dr. Ware. “He comes to us highly recommended in his profession and it is hoped that

he will meet with a hearty welcome from our citizens, as a first class physician in his line has long been needed here.”

Upon his arrive in the spring of 1893, Dr. Ware advertised his veterinary practice in the local newspapers. The notices said that Dr. Ware’s

practice included horses and cattle. Ware also kept a supply of medicine for sale.

Ware and his family moved into the Evansville House, the former location of Dr. Lucas. Dr. Ware also operated a livery stable. His wife was a

talented musician and started to teach piano and organ lessons. She later opened a musical instrument store and sold pianos, organs and sheet

music.

It was an opportune time for a new veterinarian to come to Evansville. Farmers were being encouraged to specialize in raising cattle. The all-

purpose cow was becoming a thing of the past, according to the experts who spoke at local farmer’s institutes. Evansville area farmers began to

improve their dairy cattle in order to produce a better quality product to sell to the local creameries. Others started beef cattle herds.

There was also great interest in horse racing. A horse race track on the southwest edge of Evansville opened in the spring of 1893. Joe Wonder

was the most popular race horse in Evansville at the time and he won races against horses from Janesville, Stoughton and other nearby towns.

Nancy Hanse, Princess Wilkes, Headlight, and Rowdy Boy were other popular Evansville race horses.

As the value of cattle and horses increased, the Evansville area farmers and horse owners were willing to spend more on the health care of their

animals. A professional veterinarian was an asset to the community.

Dr. Ware also offered his services one day a week in Brodhead. In July 1895, Ware announced that he would have office hours at Graham’s

livery, every Monday.

Dr. Ware moved his livery stable and veterinarian business frequently. In April 1900, Dr. Ware purchased a building on East Main Street that was

used as a livery by Charles Winship. He paid $1,700 for the building. The family moved into the second story of the livery.

In 1903, he made an addition to the building, to accommodate his growing livery business that he operated with his nephew, Ernest Bazley.

Shortly after making the addition to the livery, he sold it and rented a building on North Madison Street. Then, a few months later, Dr. Ware moved

again. Within a span of five years, Dr. Ware moved at least six times.

Agnes Ware died in January 1906, from injuries received in a fall down a flight of stairs. In August of that same year, Charles Ware married

Margaret Francis Munger, Evansville’s first woman to serve as a rural mail carrier. Shortly after they were married Ware moved to the Marge

Munger’s farm west of Evansville, then returned to Evansville a short time later.

Evansville area cattle were threatened with an outbreak of bovine tuberculosis in the early 1900s. The bovine tuberculosis could spread to

humans by drinking unpasteurized milk from diseased cows.

In December 1908, tuberculosis was discovered in a herd of cattle in Magnolia township. Robert Acheson, a butcher in Magnolia bought an

animal from a farmer and when it was slaughtered, he found signs of tuberculosis. The entire herd was quarantined.

A month later, the herd of seventeen cattle owned by John Finneran in Magnolia was tested for tuberculosis. Three of the cattle tested positive for

the disease and were destroyed.

Several issues related to the health and well-being of animals came to the attention of residents in the Evansville Area. The Wisconsin Anti-

Tuberculosis Association was active trying to educate the public about the dangers of tuberculosis. Sales of the Anti-Tuberculosis stamps served

as a fund raiser to support the association’s pamphlets and other educational materials. Some experts estimated that 55% of the cases of

tuberculosis were spread from cattle to humans.

The spread of tuberculosis from dairy cattle to humans endangered the dairy farmer’s ability to maintain a productive business. This was

illustrated in a May 1910 news release published in the Evansville Review.

Dr. David Roberts, the State Veterinarian in 1910, issued the following statement about the disease. “Bovine tuberculosis is costing the United

States millions of dollars yearly, not through the actual death of tubercular animals but by the tubercular animals infecting the healthy ones,

thereby reducing their actual value,” Roberts said.

Dr. Roberts recommended that farmers have their animals tested animals for tuberculosis. “When this information reaches the livestock owner, I

am sure that he will be more anxious to wipe tuberculosis out of his herd than anyone else, owing to the fact that he is financially interested and he

and his family first of all are consumers of the products of cattle.”

Evansville dairy herds were not immune to the disease. Following the outbreak in 1908, there was another in 1910. A local veterinarian reported

that two dairy cattle in the Evansville had tuberculosis. The animals were killed to prevent the spread of the disease.

Patrons of local dairies were also warned to purchase milk that was pasteurized to prevent the spread of tuberculosis. One local dairy was the

victim of rumors that he did not properly process the dairy products and he took immediate action to clear his name. Dairy owner, D. R. Meloy

placed the following ad in the January 1911 issues of the Evansville Review: “To the Public. The rumor that I am not pasteurizing my milk is false

and without foundation. Every particle of milk and cream I handle is thoroughly pasteurized and cooled.”

Human treatment of animals also was a growing concern among Evansville residents. An effort was made by the State Humane Board to organize

a branch in Evansville. Petitions were circulated to get the names of those who were interested in “relieving the suffering of our dumb animals.”

Enough people signed the petitions to form a humane society. Although these first efforts lasted only a few years, it drew attention to the plight of

horse and other animals that did not receive proper care.

By 1910, three men were practicing veterinary medicine in Evansville. Dr. Charles Warren Winship was a licensed veterinarian and owned a livery

stable. When he died in June 1911, his obituary said that he had practiced his profession for many years.

Dr. Charles S. Ware had an active practice and also operated a livery stable. In March of 1910, he put his livery and his horses, buggies,

harnesses and other equipment up for sale.

A new veterinarian arrived in Evansville in the spring of 1910. Dr. Rudolph E. Schuster was a graduate of the Lodi High School and the McKillip

Veterinary College in Chicago.

In 1910, Dr. Schuster purchased the livery stable of Dr. Charles Ware at 115 East Main Street and maintained his office there for the duration of

his 30-year career in Evansville.

Upon his arrival, Schuster immediately placed advertisements in the local newspapers. One newspaper, The Enterprise also added a short article

about the new veterinarian. “R. E. Schuster, M. D. V., has an advertisement in this issue of the Enterprise, calling the attention of horse owners

and stockmen to the fact that he is looking after veterinary work in and about Evansville. Mr. Schuster has recently located here, is a graduate

veterinarian from Madison, and people needing his services will find his office located in the livery barn formerly occupied by C. S. Ware.”

Dr. Ware moved his veterinary practice to a building on North Madison Street, just north of the Bank of Evansville. For many years, the two

veterinarians competed for local business and their advertisements often appeared next to each other in the local newspapers.

Charles Ware was appointed local assistant state veterinarian in November 1911. In order to get the appointment, Dr. Ware passed a civil service

examination and was chosen by the State Veterinarian. His territory included the counties of Rock and Green. Although he had been a liveryman

for many years, Dr. Ware was one of the first to purchase an automobile to work his territory.

For a short time, Dr. Rudolph Schuster was a single man and lived in the Commercial House hotel. When the census taker came around to do the

federal census in June 1910, Dr. Schuster told the recorder that he was 26 years old and a boarder at the hotel.

A year later, on June 7, 1911, Rudolph Schuster married an Evansville woman, Uva Griffith. He improved the living quarters above the livery

stable, and had a new foundation built under his barn. The Schusters moved upstairs over the livery and lived there for many years.

Dr. Schuster was active in the Wisconsin Society of Veterinary Graduates. The organization met twice a year and in July 1912, the program was

held in Janesville. Dr. R. E. Schuster presented a paper at the meeting.

There was enough business so that the two veterinarians were kept busy. Evansville farmers were bringing in railroad car loads of sheep and

cattle. Dairy farmers had a ready market at the D. E. Wood Butter Company and increased their herds to meet the demand for milk and cream.

Beef cattle raisers and horse owners were acquiring award winning livestock with excellent breeding.

Valuable animals and the occasional rare disease called for the skills of the veterinarians. Occasionally the animal doctors were stumped or

needed assistance. The difficult cases made the news. When Henry Apfel’s valuable mare came down with lockjaw, all the best veterinary skills

could not save the horse.

Local, state and federal veterinarians were called out in the summer and winter of 1914 to save the investment of livestock owners. In July a

report of hog cholera on the John Gillies farm caused some alarm. Guss Buss rented Gillies’ farm and was raising pigs. The pigs had been

vaccinated about four weeks before the cholera was discovered, but the disease already had infected the animals. Several remedies were offered

to cure the cholera and prevent its return.

The first report of hog cholera appeared in the July 30, 1914, Evansville Review. Dr. A. H. Faunce of the Federal Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S.

Department of Agriculture offered this advice: “Charcoal is a very good thing to feed to hogs in any danger from this disease. Also a little

turpentine mixed with soft feed will do good, by tending to eliminate worms. Liquor cresolis compositis is recommended by the bureau of animal

industry at Washington as a good disinfectant and is used by them in their work. It is best when used in proportion of one gallon to thirty gallons of

water, and applied with a spray pump. Lime sprinkled around the pens occasionally is a very beneficial thing whether there is danger of cholera or

not.”

Farmers were also warned to clean the area where pigs were kept and they were urged to stop the spread of the disease. Dogs, birds, and

humans could spread the disease, according to Faunce.

Dr. Faunce offered his services as a free lecturer to “Farmers and their organizations, commercial clubs, veterinarians, etc.” Faunce included

demonstrations on vaccinating animals, disinfecting pig pens, and other preventive measures farmers could take to prevent the spread of the

disease.

The information came too late for Guss Buss. He lost 25 pigs to the disease in July, but the scare was quickly over. Stockmen continued their

usual routines, traveling with animals to fairs, and bringing animals to the farm to feed and fatten for the market.

Then a serious epidemic occurred in the fall of 1914. It was the dreaded hoof and mouth disease. Before the disease was eradicated, animals in

22 states and the District of Columbia were affected.

In late October, Dr. Rudolph Schuster was called to the farm of Chester F. Miller in Porter township. Miller was a stock buyer and for several years

had purchased feeder cattle in large lots, brought them to Evansville by railroad car, and placed the animals on farms to finish for the Chicago

meat market.

In the fall of 1914, Miller was doing his usual fall work. He brought two car loads of feeder cattle from Chicago stock buyers. Sixty head of cattle

were delivered to the depot in Evansville and driven over the country roads to the Miller farm. Within a few days, Miller discovered some of the

cattle were sick.

He called in Dr. Rudolph Schuster to examine the sick animals. Dr. Schuster recognized immediately that he was dealing with a serious outbreak

of hoof and mouth disease. Schuster telephoned for a State Veterinarian to come to the farm and confirm his suspicions.

Dr. O. H. Eliason was given the assignment and he wasted no time in getting to the Miller farm. Eliason confirmed that Dr. Schuster’s diagnosis of

hoof and mouth disease was correct and immediate action was taken to quarantine the Miller farm, and the people and animals residing there.

The U. S. Department of Agriculture was already dealing with the outbreak in several other states. Miller’s farm was one of the first in Wisconsin to

be confirmed with hoof and mouth disease. Six federal meat and animal inspectors were called to Miller’s farm to examine the livestock.

The federal veterinarians placed the Miller farm under quarantine and guarded the farm 24 hours a day to make sure that no animals or people

came or went from Millers. The inspectors were also concerned that farms along the route the cattle had been driven were affected and the

disease could spread to other animals that traveled the roads.

The inspectors brought in scrapers to dig a trench, twenty rods long; twenty feet wide and 10 feet deep. All of the animals on the farm were driven

into the ditch and slaughtered. Miller had a large livestock operation. The small shipment of sick cattle that he had received from Chicago cost

Miller a large investment. He lost all the livestock on his farm.

Federal agents killed 101 head of cattle and 300 sheep on the Miller farm. The bodies were covered with quick lime and buried under five feet of

dirt. The farm dog and the chickens were spared, but they had to be dipped in a strong disinfectant so that they would not spread the disease.

The farm yard around the animal pens was plowed and the buildings were disinfected. Every inch of the farm was to be cleaned, if possible. The

disease was so dangerous that it could be spread by fodder, manure, saliva, and hides.

Federal veterinarians wore rubber boots and rubber coats and had to be fumigated each time they left their work to go the farm house. No one

was allowed on or off the Miller farm. The farm buildings were washed with disinfectant and fumigated to rid the structures of disease

One week after the Miller animals were cleared, no new cases had been reported near Evansville. However, within days, Rock County farms, in

Johnstown and Bradford township were affected and the entire State of Wisconsin was placed under federal quarantine.

Miller was promised by the federal and state agents that he would be reimbursed for the price of the meat. The federal and state governments

shared the cost of reimbursement. However, there was still a great loss to Miller. His farm was quarantined for six months and no animals could

be brought to the farm. .

The Arthur Franklin’s farm, adjacent to the Miller farm, was also suspected of having animals infected with hoof and mouth disease. Farmers who

had animals that shared the same stream that the Miller cattle drank from were also inspected. The disease was so dangerous that even a drop

of saliva could carry the disease. Farmers were urged to report any signs of infection in their animals. Sore mouth, slavering, fever, and

lameness were listed as warning signs of the disease.

Evansville farmers were not alone. By mid-November sixteen states were under quarantine. In Wisconsin, more than 100 herds were examined by

federal and state agents. Many farm animals were killed and farm families were confined until their farms were considered safe.

The entire state was quarantined. Any livestock moved from one place to another had to be inspected and certified free of disease by one of the

state veterinarians.

Federal agents ordered railroad cars to be cleaned and disinfected before use. They were especially concerned about the animals from the

nation’s stockyards.

Shipments to and from the Union Stock Yard in Chicago came to a halt. For the first time in fifty years the Union Stockyards in Chicago closed.

The closings lasted for ten days, while the yards were cleaned and disinfected.

After the quarantine was lifted, any animal going to the Chicago yards had to be certified free of disease by a federal inspector or an accredited

veterinarian. The National Stock Yards at East St. Louis and the stockyards in St. Joseph, Missouri were also closed.

The hoof and mouth outbreak forced the cancellation of Chicago’s November International Livestock Show, a popular show that drew livestock

farmers and buyers from around the world. Evansville’s best beef and sheep farmers usually had animals at the show and realized large profits

from the sales made through contacts at the show.

The 1914-15 hoof and mouth disease epidemic on farms near Evansville greatly reduced the stock shipments out of Evansville and hurt the

income of farmers that did not have herds infected with the disease. Even after the Union Stock Yards in Chicago reopened, shipments nearly

came to a halt.

Both of Evansville’s veterinarians, Dr. Charles Ware and Dr. Rudolph E. Schuster, were graduate veterinarians. Before the 1914-15 outbreak of

the hoof and mouth disease in Wisconsin, graduate veterinarians were allowed to inspect and certify animals for shipment out of state.

With the outbreak, state and federal veterinarians took control of all animal shipments. Any animal going to the Chicago yards had to be certified

as free of disease by a federal inspector or an accredited veterinarian.

Before the epidemic, sheep were driven over the dirt roads from the farm to the depot. Fearing that the roads were contaminated with the hoof

and mouth disease, Evansville farmers loaded their livestock into farm wagons or sleighs and delivered them to the stockyards at the depot.

In early December 1914, several hundred sheep were brought to the depot by Chris Jorgensen and Robert Hubbard. Two veterinarians, one from

the state and one from the federal government were at the depot to inspect the sheep. The animals were given a clean bill of health and cleared

for shipment.

On January 22, 1915, the United States Bureau of Animal Industry announced that the counties of Brown, Dane, Dodge, Jefferson, Langlade,

Racine, Rock, Walworth, Washington, Waukesha and the townships of Exeter and Brooklyn in Green County were placed in modified territory.

This meant that the quarantine was lifted, if there were no infected or exposed farms within a five miles radius of the farm. This partial lifting of the

quarantine meant that after inspection by a veterinarian, the stock scheduled for immediate slaughter could be sent to Chicago’s Union

Stockyard.

During the outbreak only the state and federal authorities could certify that animals were free from the disease. With the partial lifting of the ban

on shipping animals, the federal government allowed the state certified veterinarians to inspect only the livestock that was sold in the Milwaukee

market.

In early February, a federal inspector announced: “As far as we know there is not a single case of foot and mouth disease in Wisconsin. We

hope to have the quarantine lifted entirely by March first.” The epidemic had a long term affect on the livestock farmers in the state as more state

and federal regulations were put in place.

Due to the outbreak of foot and mouth disease in Wisconsin, the Live Stock Breeders’ Association postponed their 1915 annual meeting. The

meeting was usually held in the early months of the year and included exhibits of prize animals. Several Evansville area farmers, including John

Robinson, a Hereford and sheep breeder, were active participants in the organization. None of the breeders wanted to risk spreading the disease

by bringing animals together for show purposes.

The hoof and mouth outbreak also created a shortage of good breeding stock in the United States and in the world. War in Europe and shortages

of livestock created a market for animals free of disease.

Arthur G. Leonard, president of the Union Stock Yard and Transit company of Chicago told farmers that the era of the successful livestock raiser

was about to begin. In the January 1915 issues of the Chicago Farmers’ and Drovers’ Journal, Leonard said: “There is not a single cloud on the

horizon of future prosperity for the growth of cattle and sheep in this country, while the hog has always been at once the ‘mortgage lifter’ of the

farm. On the whole the live stock industry of the United States is on the eve of a period of prosperity for those who enter it wisely. Those who are

first in the field and work steadfastly for the industry will reap the greatest rewards.”

The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture also encouraged the stock breeders to improve their herds and to breed only animals that were free

from disease. The state’s focus had been on eliminating tuberculosis and after the epidemic there was a renewed effort to rid the state’s cattle

herds of tuberculosis.

The state veterinarians urged farmers to have their herds tested and offered a free tuberculin test. The veterinarians emphasized that the testing

was voluntary but incentives were offered to encourage participation.

Because of the epidemic, there was expected to be a demand for meat free from disease. If the herd tested free of the disease, the farmer

received state certification and the state kept a record of the testing that was available to other breeders and stockyards. The state veterinarians

urged local and state fairs to hold special exhibit classes for herds and animals that had tested free of tuberculosis.

The Wisconsin Legislature of 1915 passed laws, known as Chapter 625. The new laws gave the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture authority to

appoint veterinarians to inspect stock for interstate shipment. The law also provided penalties for those who made shipments without getting

inspection. This gave state appointed local veterinarians new authority and potentially new business.

Dr. Rudolph Schuster maintained his membership in the Wisconsin Veterinary Society and was kept informed about new developments in

veterinary science through his association with other veterinarians. Many of Dr. Schuster’s clients were in Magnolia township. Over the next few

years, he regularly attended animals on the farms of Ed Larson, Gene Rowald, Charles Davis and Wilbur Andrew.

Another Evansville veterinarian, Dr. Charles Ware, was involved in planning the Rock County Fairs held at the fairgrounds in Evansville. He was

especially interested in the horse races and served as superintendent of that event.

Evansville’s fair was one of the stops on the racing circuit for trotters and pacers. Dr. Ware organized the races and was able to obtain some of

the “fastest steppers” in the country. There were racers from Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois entered in the competition.

The Horse Review of August 1916 praised Dr. Ware’s work. “It was only a few years ago that Evansville, Wis., was a mere fly speck on the racing

map of the west. Today it boasts of one of the best conducted half-mile track race meetings in the country. Doctor Ware has labored incessantly

to give his fellow-citizens real horse-racing. He has overcome many obstacles and made good in a manner that admits of no argument.”

Ware also had his own farm on the western edge of Evansville. He raised hogs and kept cows to provide milk for his dairy.

In 1917 there was an outbreak of hog cholera in the Rock County and farmers were urged to take precautions. A Janesville Gazette article about

the disease cautioned farmers: “If cholera is in your neighborhood, use the same precautions to keep from getting it on your farm as you would

use if there were an epidemic of small pox or scarlet fever.” Farms that had hog cholera were required to place a sign on their premises

announcing the disease.

The hog cholera was devastating and farmers were urged to get a veterinarian to kill the diseased animal and examine the intestines, kidneys,

glands, and other organs. If the veterinarian’s examination proved that cholera was the cause of the illness, then the farmer was urged to have

the rest of his hogs vaccinated.

The State Department of Agriculture and the University of Wisconsin Department of Agriculture encouraged farmers to use the services of a

licensed veterinarian and avoid home remedies. “Do not attempt to vaccinate the hogs yourself,” the article warned.

Two outbreaks of disease were reported in the Evansville area 1919. The first was the discovery of tuberculosis on the farm of Ernest Miller, on

Finn Road.

Miller had purchased nineteen head of milk cows and heifers from a farmer in Illinois. The seller had assured Miller that there was no need to

have the animals tested and Miller trusted the seller.

After purchasing the animals and bringing them to his farm, Miller offered the cattle for sale. Wisconsin law required that the animals be tested

and Miller called in Dr. Rudolph Schuster to perform the tuberculosis test. It was positive on 16 of the 19 head of cattle that Miller had brought in

from Illinois.

The animals were shipped to Milwaukee where they were slaughtered and inspected by federal veterinarians. The news of the tuberculosis

incident highlighted Wisconsin’s strict laws for preventing the spread of disease among the livestock herds.

According to the Review report of the incident, “The carcasses of those which are fit for meat will be sold, and those which show too much

tubercular will be thrown away. The loss will fall on Mr. Miller. This experience will not be a very good advertisement for Illinois cattle. If Illinois

laws had required that the cattle be examined before shipment, the railroad would not have accepted the cattle for shipment.”

A second outbreak of disease in 1919 was of rabies, brought to the Magnolia area by a rabid dog. The dog was killed near the Locke Pierce farm

and brought to Dr. Rudolph Schuster to examine.

Dr. Schuster removed the head of the dog and sent it to the biology laboratory at the University of Wisconsin for inspection. The tests proved that

the dog had rabies.

Before it was killed, the rabid dog bit a six-year-old boy, Howard Dougherty. The authorities suspected that the animal had also bitten several

other dogs. The Dougherty boy was given a series of shots, known as the Pasteur treatment to keep him from getting rabies.

Several other dogs were killed after they showed signs of the disease. Evansville’s Police Chief, Fred Gillman warned citizens to muzzle their dogs

and keep them tied up until it could be determined that no other animals had been bitten.

In an article in the Review, Gillman warned readers that it could take up to four weeks before any symptoms would appear, after an animal or

human was bitten by a rabid animal. “As it takes so long for the disease to make its appearance it is very probably that the ban on dogs running

at large will be continued for some time yet, as the authorities here are determined to take every precaution against this terrible disease.”

Evansville’s veterinarians served in civic capacities in the early 1920s. Dr. Charles S. Ware was secretary of the Rock County Fair held in

Evansville and was primarily responsible for the livestock and the harness racing. Dr. Rudolph E. Schuster was appointed to the Evansville City

Council in August 1918 and was reelected for several terms.

Both veterinarians advertised their services in the 1920s and helped to improve the health of the livestock in the rural areas surrounding

Evansville. Dairy and livestock provided a stable income for area farmers, as long as they could provide healthy animals to the livestock markets.

Dr. Ware was a supporter of the movement to bring young people into the business of farming. He supported the calf and pig clubs that were

forerunners of the 4-H movement. Ware owned Chester White pigs and with other area hog raisers offered the “Chester White Cup” as a trophy

for raising prize winners in the hog contests.

Ware and his wife also owned a dairy in Union township, west of Evansville, and had a regular market for their products in Evansville.

In some parts of the United States there was a decline in horses and other livestock and some veterinarians turned to small animal service. The

Evansville veterinarians did not follow that trend, as area farmers continued to increase their dairy and livestock herds.

Large shipments of sheep and feeder cattle were brought to the Evansville area, and there was a ready market for milk from the local dairy

farmers. The D. E. Wood Butter Company provided a local market. Healthy animals were a key to successful marketing of farm animals and their

products.

In the early 1920s it was not unusual for some farmers to lose an entire herd of dairy cattle to tuberculosis. In November 1920, an Orfordville

farmer lost thirty head of “high grade Holstein cattle” after they tested positive for tuberculosis. The entire herd was taken to Madison for

slaughter. The Review noted that at a normal price, the cows would have brought between $120 and $200 a head. This did not include the value

of the milk and calves that might have been produced.

Wiping out tuberculosis was a goal of the Wisconsin State Veterinary service. Hogs and cattle had been found to have the disease.

The State Veterinarians issued a statement sent to the Review: “The tuberculosis menace is getting serious in Wisconsin, not only to the health of

the people of the state, but to those who raise hogs for the market. Meyer Bros., the Madison packers, state they recently purchased a car of

Wisconsin raised hogs on which they were forced to stand a loss of 40 percent on account of the presence of the disease.” The article concluded

that, “There should be a general awakening of the farmers and breeders in Wisconsin regarding this menace.”

The cost of the animals with tuberculosis was passed on to the farmer, with reduced prices. Animals sent to Chicago markets from Wisconsin were

also receiving huge cuts in prices, as the disease was detected and the packers refused to buy them.

Dr. Schuster’s business in testing for tuberculosis was greatly increased as local farmers realized the loss they suffered, if packers refused their

animals. In the fall of 1923, Schuster tested the herds of Ed and Vern Ellis, Gilbert and Byron Amidon, John Hanson, Adelbert Smith, Herman

Fenrick, Ed Julseth, Earnest Bayliss, George Schumaker, Henry Knudsen, Ben Vigdal, Wayne Lewis, Richard Babcock, Clarence George, Royal

Clark, and Charles Ware.

When he went to the farms to do the testing in October 1923, Dr. Schuster found some herds of dairy cows that were nearly clean. In other herds

he found that half of the animals reacted positively to the tuberculosis test.

It did not take long for the local dairies to pick up on the fact that they needed to reassure their customers that their herds were free of disease.

The Bonnycroft Dairy owned by O. H. Perry and his son Stanley, provided milk and cream to Evansville merchants and households. They

advertised that their herd had been tested. “Perry Cream Is Clean Cream” was included in their advertisement in the local newspaper.

By 1925, Chicago dairy markets were threatening to reject milk from Wisconsin dairymen, unless they could prove that their herds were free of

disease. Wisconsin farmers signed petitions to get the State to provide free testing for tuberculosis, so that they would not lose their market for

local and out-of-state sales of dairy products.

Wisconsin passed a law to require dairy herds to be tested and the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture offered the test free of charge. Diseases

in some Wisconsin herds threatened all others who wanted to market their dairy products.

There were heavy fines for farmers who refused the tests. There was little need to convince area farmers to have their herds tested, as they

realized the loss to their farm income, if no one would accept their products.

Veterinary services were required for other diseases and accidents on Evansville area farms. Hog cholera reappeared in Rock County in October

1921. The University of Wisconsin-Extension provided a serum for farmers to use in vaccinating their herds. Farmers who vaccinated their own

herds often did not follow the directions supplied with the serum. State Veterinarians issued news releases stating that the vaccinations were

ineffective if the directions were not followed.

In addition to disease, there were other significant loses. Dr. Schuster was called to the farm of Carl Carlson in June 1921 to check on Carlson’s

hogs. Schuster discovered that they had all been poisoned. Someone had mistakenly put a poison that was used to destroy insects, called, Paris

Green, into the slop barrel and it was fed to the pigs. Dr. Schuster could do nothing to save the hogs and twenty-two of the twenty-seven herd

died of the accidental poisoning.

Farmers were increasing the number of feeder animals brought to Evansville. In the early 1920s, thousands of sheep were shipped from western

states in the fall of the year and driven to farms in the Evansville area. Through the winter months, the sheep were fed and fattened for the

Chicago markets in the spring, bringing a nice profit for area farmers.

In late September 1923, a large shipment of 9,000 western lambs were brought by railroad cars into the Evansville stockyards. The lambs were

purchased in Montana and shipped from White Sulphur Springs, Montana, by W. W. Gillies and Lloyd Hubbard. The train stopped in Montivideo,

Minnesota, where the lambs were fed and watered. The animals were reloaded for shipment to their final destination in Evansville.

When the train arrived in Evansville, Gillies and Hubbard discovered that several of the lambs were dead and others were sick. State and Federal

veterinarians were called to investigate the illness. They were concerned that the stockyards holding the animals might be contaminated with

disease.

The State and Federal examiners determined that there was no disease present in the animals. The veterinarians decided that the food and

water the sheep had consumed along the route had contained something that was poison. Gillies and Hubbard were relieved to find that their loss

was only about 1 ½ percent of the shipment.

Within a year, the number of sheep coming into the Evansville stockyards for shipment to local farmers had increased to more than 20,000

animals. In the fall of 1924, more than 26 area farms were reported as holding imported sheep for winter feeding.

“Money In Sheep” was the headline in the Review, when the president of the Chicago Wool Growers’ Commission, Co. surveyed the holdings of

Evansville area sheep holders. Farmers were urged to borrow money to purchase sheep, if they did not have cash available.

“There should be no trouble in borrowing money to buy the lambs without additional security besides the lambs themselves, as with the feed the

farmers of this county have on hand, there is no possibility of losing money.” However, he also warned buyers to beware of animals that were

diseased. “Western growers have a trick of passing a lot of culls off onto buyers, hoping that they will not be noticed in a large flock.”

The increased animals on the farms also increased the work for the two area veterinarians. Dr. Schuster began improving his living quarters and

office at 115 East Main. The first remodeling was a fireproof exterior finish known as Kelastone put on in 1922. The Kelastone was a cement

material, similar to stucco, that covered the wood frame building.

Two years later, in 1924, Schuster built a wood frame barn with a cement floor on the south side of his building. The building was known as the

“Schuster Sales Barn” and was used by Fred Luchsinger as a sales barn for horses. It was a 16 foot extension on the lower floor of the Schuster

building. It was convenient for both Schuster and Luchsinger as he could have the animals tested for the sales.

The new addition had a cement floor. There were 24 stanchions and 2 box stalls that were fitted with drinking cups. Luchsinger’s first sale was

held in February 1925 with Dan F. Finnane, a local auctioneer, “crying” the sale.

Eradication of tuberculosis in dairy herds dominated the work of Dr. Rudolph E. Schuster and Wisconsin State Veterinarians in 1925 and 1926.

Rock County dairy farmers joined together in a petition to the State Agricultural Department requesting that every dairy herd in the county be

tested for T.B.

The editor of the Evansville Review urged farmers to attend a meeting with John D. Jones, the State Agricultural Department Commissioner, to

learn more about the testing. Headlines in the July 9, 1925 issue of the Review read: “If Area Test Is Not Adopted in County, The Dairymen Will

Lose.”

The article gave several important reasons that the dairy farmer should comply with the veterinarians performing the tuberculosis testing. “The

possibility that there may be a loss from seven to ten percent when a farmer’s cows are examined, in diseased animals, should deter no one from

having their herds examined and cleaned. For a number of animals to feed and milk, when there is no market for their product, is not as profitable

as a good market for the product from a less number of animals.”

A farmer’s refusal to have his herd tested also reduced his chances of getting loans from banks. Some bankers allowed dairy herds to be used as

collateral for farm loans. With the possibility of tuberculosis being present in untested herds, lenders threatened to stop financing farmers who

refused to have herds tested.

Untested herds were financially devastating to farmers. There were reports that butter manufacturers and dairies paid 25 cents more per hundred

for milk from tested herds than from untested herds. Some purchasers of whole milk refused to buy products from farmers with untested herds.

After hearing Commissioner Jones’ proposal to test dairy herds in Rock County, farmers signed a petition requesting testing. The tests were

made by authorized veterinarians who went from farm to farm. If there were cattle that reacted to the test, then they had to be retested at the end

six months.

Dr. R. E. Schuster was notified that the State testers would begin work in Rock County in January 1926. Each tester was assigned a township and

went from farm to farm. Every herd in the township was tested. If farmers refused the testing, their herds were quarantined and no milk or milk

products from that farm could be sold.

If cattle reacted to the test, the veterinarian determined the value of the animal. The animal was then slaughtered and the state paid the farmer a

maximum of $40 on common livestock and $90 on pure-bred stock.

Most farmers and dairymen in the Evansville area voluntarily had their animals tested for T. B. Only a few threatened to boycott the required

testing. Advertisements for dairies that delivered milk to homes and businesses, farm auctions and dairy cattle sales often carried the notice that

there was “T. B. Tested cattle” or “not a reactor in the herd.”

There were numerous reports that poultry also had tuberculosis. During the testing for tuberculosis in cattle, the veterinarians also checked for

tuberculosis symptoms in flocks of poultry.

By mid-January, the Evansville area testing was well underway. Dr. Schuster reported that no farmer had refused the test and less than 10

percent of the herds reacted and had to be retested.

The Jug Prairie area, west of Evansville, was one of the first in Rock County to be tested. George Mabie’s herd of Guernseys, H. A. Knapp’s Dairy

herd of Holsteins, and Lloyd Hubbard’s herd tested free of T. B.

However, there were some farmers that were no so fortunate. The January 14, 1926 issue of the Review said that there were some herds with

nearly 90% of the animals reacting to the test.

“That the test may work a hardship upon some is not be denied; but to leave a 90 percent herd to spread the terrible germs of a terrible disease

to hundreds of human beings is far worse. So while it may hurt some farmers and some bankers and business men, the sooner they take their

medicine, the less of it there will be to take, for the county at large has decided that it must be protected against T. B.”

A new state law was passed that helped prevent further spread of tuberculosis. Wisconsin State Commissioner of Agriculture, John D. Jones, Jr.

sent out a news release in May 1926, that all animals shipped into the state had to have a health certificate stating that they had tested free of

tuberculosis.

The cattle were to be held in quarantine until they could be tested by a veterinarian authorized by the Wisconsin Agricultural Department. “The

new regulations are designed to prevent the introduction of diseased cattle into areas which have cleaned up in the bovine tuberculosis

eradication campaign,” Jones said in the announcement.

Some farmers needed no government or peer pressure to test their animals. John Elmer and his seven sons lived just over the county line in

Green County. Elmer voluntarily tested his herd for nearly twenty-five years before others were required to have their herds tested.

Elmer told a Review reporter that his herd had always tested free of tuberculosis. By 1927, four of John Elmer’s sons had established farms of

their own, Henry on the home farm; John, Jr. Casper, and Paul on farms of their own. All were expected to follow the example of their father.

Considering that in 1929 approximately 86 percent of a Wisconsin farmers’ income came from livestock and livestock products, any disease was a

threat. Estimates were that 52 percent of the farm income was from milk, 13 percent from hogs and 11 percent from cattle and calves.

As the danger of tuberculosis was reduced, an infection that threatened to be even more dangerous was spreading. In January 1929, Dr.

Schuster worked with government officials to organize a meeting of dairy farmers to learn more about an infection called contagious abortion.

The infection was costly to the farmer, as he not only lost calves but also lost potential milk production. If the disease was present, the output of

the average cow was reduced. A healthy cow was expected to give milk enough to produce 200 pounds of butter per year and if the infection was

present the output was reduced to 100 pounds of butter or less.

The disease was described as “one of the worst cattle diseases in existence today. More loss is caused to dairymen on account of contagious

abortion than from tuberculosis.”

The state specialist, Dr. D. V. Larson, came to Evansville to talk with local dairy farmers about this disease. About 25 farmers were present at the

meeting.

Although contagious abortion had been a problem in dairy herds for many years, no cure had ever been found. Larson knew that some farmers

were still relying on home remedies and patent medicines.

Dr. Larson told the farmers that the medicines offered through drug stores and other outlets were ineffective. The only way to get rid of the

disease in their herds was to have them tested and the diseased animals had to be culled. At the meeting Dr. Schuster gave a demonstration of

how the blood test on the dairy cow was performed and farmers were encouraged to continue to have their animals tested for the disease, as they

did for tuberculosis.

Dr. Rudolph Schuster was the only practicing veterinarian in Evansville in the late 1920s. Dr. Schuster continued to operate out of his offices at

115 East Main Street and advertised: “All calls promptly answered day or night. Phone 109.”

Through the late 1920s the horse sales were held at the Schuster barn on the south end of the veterinary office. When Dr. Schuster’s sales barn

became too small for the sales, they were moved to the stockyards near the depot, or to the former fairgrounds at the southwest corner of

Evansville.

Schuster also continued to serve on the City Council and was appointed a committeeman on the Fire and Police Committee, Sanitary Committee

and License Committee.

Dr. Charles S. Ware remained active in organizing Evansville’s Rock County Fair until it was sold to the Janesville Fair in 1928. Dr. Ware kept

busy with his daily delivery of milk and dairy products to customers in Evansville. In the winter he used a bob sleigh to make his rounds and in the

summer a horse-drawn wagon.

By 1929, Dr. C. S. Ware had stopped advertising services as a veterinarian. Although he did not retire, he had health problems.

In February 1929, Dr. Ware was finishing his milk route when his team became frightened and ran away. The sleigh tipped over and Dr. Ware was

thrown to the ground and lay there unconscious. He had only slight injuries and recovered from the accident.

Through the 1930s, Dr. Rudolph E. Schuster was the only practicing veterinarian in Evansville. Dr. Schuster’s only competition came from local

drug stores as they sold “veterinary and poultry remedies.”

There was a shift in the types of animals that Dr. Schuster served in his practice. In the 1930s, the dairy cattle, registered beef cattle, hogs, and

sheep, were the animals most often treated by Dr. Schuster.

As more farmers purchased tractors, the number of horses on the farms declined. Some farmers in the Evansville area preferred using horses for

farm work and several had registered work horses that were also kept for breeding and horse shows.

The State Department of Agriculture estimated that 86 percent of the gross income of Wisconsin farmers came from livestock and livestock

products. Dairy products were estimated to bring in 52 percent of the income; hogs, 13 per cent; and cattle and calves, 11 percent.

During the Great Depression, the federal government urged farmers to reduce the numbers of livestock. First, the federal government authorized

payments under a plan called hog and crop reduction. They urged farmers to reduce the number of hogs kept on farms and to take crop land out

of production. Later, they urged farmers to reduce the dairy output. It was hoped that this would increase the amount farmers were paid for their

products in the marketplace.

There were no major outbreaks of disease in the 1930s, as there had been in earlier times with hoof and mouth disease and tuberculosis. There

was a persistent problem with the disease known as contagious abortion. The disease was often called Bang’s or undulant fever, common names

for brucellosis.

There was some danger to humans, in that the disease could be spread through consumption of milk that was not pasteurized. Farmers and

employees of slaughterhouses or butcher shops could also become infected with brucellosis, by coming in contact with diseased meat.

Farmers were advised to sign up for a government program, so that they could be reimbursed for diseased animals in their herds. Veterinarians

were authorized by the State Department of Agriculture to test cattle for Bangs. Only authorized veterinarians could send blood samples to the

State Control Laboratory for testing. By 1935, the State of Wisconsin had 320 veterinarians that were approved for testing.

If cattle tested positive for Bangs, they were culled from the herd and slaughtered. The federal government reimbursed farmers for the animals

that were killed. If the animals were registered stock, the farmer was reimbursed at a higher rate than if they were unregistered.

An epidemic of sleeping sickness caused the death of many horses in the Evansville area in 1938. Dr. Schuster reported to the Wisconsin State

Journal in August of that year that 12 horses had died from the illness. The report said: “Although he said he has been unable to save some

horses from the disease which has been spreading throughout southern Wisconsin, Dr. Schuster added that many other horses have been

affected.”

There was little need for Dr. Schuster to advertise his services, but he continued to have a notice in the professional listing of the Evansville

Review. “R. E. Schuster, Veterinary Surgeon, All Calls Promptly Answered Day or Night. Phone 109. Main Street,” was all that was necessary to

alert those in need of the services he offered.

In July 1940, Dr. R. E. Schuster died, after a short illness. His pall bearers included Evansville businessmen and livestock dealers, Charles Maloy,

Earl Gibbs, Richard C. Deily, Lloyd Heffel, William and Fred Luchsinger.

His obituary said that Dr. Schuster was prominent in civic affairs, served several terms as alderman from the third ward. Besides many friends,

Dr. Schuster was survived by his wife, the former Uva Griffeth, two sons, Harold and William, (both were nicknamed “Doc” by high school

classmates.) Schuster was also survived by two daughters, Beatrice (Mrs. Kenneth) Cain and Beth Schuster. There were also three

grandchildren, Billy and Uva Mae Schuster and Kay Cain. His brother, Raymond and sister Edith, lived in Oregon.

Immediately, Uva Schuster put the veterinary business up for sale. The sale also included the building at 115 East Main, where the Schuster

family lived.

On July 18, 1490, the Evansville Review announced that the sale had been made. According to the press release, Dr. Harold Bunde, a licensed

veterinarian from Sullivan, Wisconsin had purchased the business and the building. The Schusters moved to an apartment on South First Street.

Bunde placed an ad in the same paper saying that he was taking over the veterinary practice of Dr. Schuster starting on July 20, 1940.

However, Dr. Bunde was unable to get the financing that Uva Schuster had required. The following week, in the July 25, 1940 issued of the

Review, Dr. Edwin W. Krueger, a licensed veterinarian of Hustisford, Wisconsin, announced that he was the new owner of Dr. Schuster’s practice.

Dr. E. W. Krueger, his wife and infant daughter, moved into the apartment vacated by Uva Schuster and her children, Beth and Bill. “Dr Krueger

comes to the city highly recommended as a veterinarian of unusual merit,” the Review reporter said in the front page article announcing the arrival

of the new veterinarian and his family.

An advertisement on page 6 of the same issue of the Review that announced his arrival read, “ANNOUNCEMENT. I have purchased the building

and equipment of the late Dr. R. E. Schuster at 115 East Main street, and am ready to serve this community with prompt and efficient Veterinary

Service. Your Patronage Will be Appreciated! Dr. E. W. Krueger, Licensed Veterinary, Telephone 109.”

Krueger was a graduate of the Cedarburg High School in 1935 and he and his distant relative, Dr. Harold Bunde had attended Ontario Veterinary

College at Guelph, Ontario, Canada. The college was part of the University of Toronto.

Both Bunde and Krueger received their degrees in 1939. Following his graduation, Dr. Krueger opened an office at Hustisford. He was a member

of the American Veterinary Medical Association, the Wisconsin Veterinary Medical Association and the Southeastern Wisconsin Veterinary

Association.

A few months after purchasing the business, Dr. Krueger began remodeling the first floor of the building at 115 East Main. A brick front was put

on the building. A new office and medical supply room was added and the treatment room’s ceiling and walls were sealed. Kruger also built a

garage on the back of the building.

Dr. Krueger was the first veterinarian in Evansville to advertise that he would provide services to pets, as well as farm animals. In March 1942,

“Leota Dog Food” was for sale at the veterinarian’s office. According to Dr. Krueger’s announcement, the food was a compound of fresh frozen

100 percent meat. Gaines Dog meal and vitamin and mineral supplements for animals were available for sale at Dr. Krueger’s office and pet

hospital.

During World War II, Dr. Krueger was called into service. Through the pleadings of livestock shippers and local farmers, the Luchsinger brothers,

Charles Maloy and Charles Boode, the U. S. Army released Dr. Krueger from service and he returned to Evansville.

As Evansville was a large livestock shipping area and had many dairy farms that produced food products, the federal government decided that Dr.

Krueger’s services were necessary to the community. He was the only practicing veterinarian in Evansville, and his services were essential to

insure that the animals bought and sold in the area were free of disease.

Evansville lost the oldest veterinary surgeon in December 1941. Dr. Charles S. Ware was ill for a number of years prior to his death. He retired

from active practice of animal medicine in the 1920s.

Dr. Ware’s obituary said that he had practiced medicine for thirty five years before he retired. His survivors included his wife, Marjorie Francis

Munger Ware; his daughter, Constance Collins (Robert Collins); his son, William Ware and a step-son, Cecil Bazley.

During World War II the nation’s food supply was important to the men and women serving in the Armed Services, as well as the people at home.

A farmer’s institute held in the Evansville High School auditorium and gymnasium in March 1942 emphasized the importance of the quality of the

farm products farmers produced.

Dairy husbandry and herd improvement were all necessary to the war effort. The veterinarians and experts from the University of Wisconsin

spoke on “The Costly Diseases of Farm Animals” and stressed the diseases mastitis and Bangs as particularly detrimental to dairy herds.

As the only practicing veterinarian in the Evansville area during World War II, Dr. Edwin Krueger had a key role to play in keeping the beef, hog,

sheep and dairy operations in business.

A program of calf vaccinations was inaugurated by the State Department of Agriculture in 1940. There were five options for farmers to use in the

program. Under four of the plans, the farmer was required to have the vaccinations done by an approved veterinarian. The veterinarian reported

to the State when the vaccinations were completed and the State issued a permit for each herd if the vaccination was done by a veterinarian.

The herd permit allowed the veterinarian to vaccinate new calves in the herd when they were between the ages of four and eight months.

Vaccinated purebred calves were identified by their ear tag number and the ears were tattooed with the letters WV, for Wisconsin-Vaccinated” and

the date of vaccination. If the farmer chose to do his own vaccinations, no permit was issued by the State.

Working with farmers and the Wisconsin Department Agriculture, the local veterinarian sent samples of milk, tissue, and blood to the state

laboratory for diagnosis. The state laboratory reported that the most common ailment in hogs was an intestinal disorder, necrotic enteritis. The

lab also tested more than 300,000 blood samples for Bangs disease. Nodular disease, an intestinal disease was the most common disease found

in sheep. Diseases commonly found in poultry were leukemia, coccidosis and pullorum.

The State Department of Agriculture continued to tighten restrictions on the sale and showing of dairy cattle, creating more work for local

veterinarians. According to a news release in the September 21, 1944, issue of the Evansville Review, The seller of a “bovine animal, except

steers” had to give the buyer the Bang’s test record at the time that any part of the purchase price was paid or the new owner took possession of

the animal. If the animal was sold at auction, a public notice had to be posted giving “the status of the herd with reference to Bang’s disease, and

complete information as to the history of the herd.”

Any animal reacting to a Bang’s test had to be quarantined to the farm by the veterinarian who made the test. All sales held in pavilions had to be

supervised by a veterinarian, chosen by the Department of Agriculture.

While dealing with the day-to-day operation of the veterinary service was difficult enough for Dr. Krueger, an unexpected tragedy forced him to

change locations for a short time in the spring of 1944. The veterinarian offices and the Krueger residence on the second floor of the building at

115 East Main were damaged by a fire in April 1944.

The Krueger’s moved to a farm west of Evansville and Dr. Krueger hired carpenters to repair the damage to the building. The workmen removed

the garage at the south end of the first floor and a storeroom, bedroom and porch on the second floor were taken down. Smoke and water had

also damaged parts of the interior of the building. Plaster in the kitchen, a bedroom and hallway of the second-story apartment was removed.

The carpenters built a new garage on the first floor. On the second floor a new bedroom, laundry and the porch were restored. The Krueger’s

returned to their restored home and office in the fall of 1944.

As a hobby, Dr. Krueger enjoyed attending dog shows. In the fall of 1944, he showed several dogs and earned a first place for a female boxer.

The shows also served as a family outing for Krueger, his wife, and daughter, Carlyn and son, Ed. The family frequently visited relatives in

Hustisford and Cedarburg and Guelph, Canada.

Theo Devine was the secretary in Dr. Krueger’s office during the 1940s. When her uncle, Staff Sergeant Lewis Devine, returned from World War

II, he brought a collection of German souvenirs. Dr. Krueger’s office window on East Main Street was used as a display case for the items

collected by Devine. Many of the items were taken from German soldiers surrendering to the United States military at the close of the war. The

collection included a swastika pennant, German guns, daggers, belt buckles, and a German helmet.

Dr. Krueger’s practice was growing rapidly and in October 1945, he brought in an assistant, Dr. Paul Starch, a recent graduate of the Iowa State

Veterinary College, Ames, Iowa. Dr. Starch was from La Crosse, Wisconsin.