Col. George W. Hall, sometimes known as

"Popcorn" Hall, is one of Evansville's famous men.

Hall was a circus owner and animal trainer. He was

known throughout the United States, Mexico, and

the Caribbean Islands.

No exaggeration is necessary in describing the life

of George W. Hall. His adventures were real and

courageous. Hall's greatness is measured as much

by his business success, as by his generosity to the

poor and disabled.

Like any showman, he loved publicity and the

drama of the circus world. With good management

and a keen sense of what the circus public wanted

to see, George W. Hall developed a family circus

business. The Hall circus grew from a small

traveling museum of stuffed birds and farm animals,

to a railroad car circus with a menagerie of exotic

animals from around the world.

His love of show business was passed on to several

generations of his family. From a very young age,

George Hall's children, grandchildren and great

grandchildren took part in the activities of the circus

business. In the 1870s, Evansville began to claim

the Hall circus as its own. It was the beginning of a

piece of Evansville history that would include four

generations.

"Popcorn" Hall, is one of Evansville's famous men.

Hall was a circus owner and animal trainer. He was

known throughout the United States, Mexico, and

the Caribbean Islands.

No exaggeration is necessary in describing the life

of George W. Hall. His adventures were real and

courageous. Hall's greatness is measured as much

by his business success, as by his generosity to the

poor and disabled.

Like any showman, he loved publicity and the

drama of the circus world. With good management

and a keen sense of what the circus public wanted

to see, George W. Hall developed a family circus

business. The Hall circus grew from a small

traveling museum of stuffed birds and farm animals,

to a railroad car circus with a menagerie of exotic

animals from around the world.

His love of show business was passed on to several

generations of his family. From a very young age,

George Hall's children, grandchildren and great

grandchildren took part in the activities of the circus

business. In the 1870s, Evansville began to claim

the Hall circus as its own. It was the beginning of a

piece of Evansville history that would include four

generations.

Article printed in the May 6, 1874,

Evansville Review, Evansville,

Wisconsin

Evansville Review, Evansville,

Wisconsin

George W. Hall knew the circus business at many

levels. He was born in Lowell, Massachusetts,

December 5, 1837 to Joseph and Susan Nichols Hall.

He was one of six children. Joseph and Susan Hall

moved to Wisconsin in 1859 and purchased a farm in

Magnolia.

Young George had his first taste of circus life at the

age of 10 and until his death in 1918, he never lost

his love for the business. According to the

Commemorative Biographical Record of Rock County,

published in 1909, "he would run away from home in

the spring, spend the summer with some circus, and

then return home in the fall to spend the winter at

home."

For a short time he worked in a candy factory in

Boston, then went to Concord and started selling

popcorn on the trains. In 1855, he went to New York

to sell popcorn. He made contact with Solon

Robinson, an editor of the New York Tribune.

Robinson had encouraged him to sell popcorn in New

York and after purchasing a supply of popcorn,

George became a popcorn vendor, also selling his

goods on the trains. Horace Greeley, another famous

New York Tribune editor, was credited with giving him

the name "Popcorn" Hall.

In March, 1855, at the age of 19, George Hall married

Sarah Wilder. Sarah shared her husband's

enthusiasm for the circus business. She was an active

participant in the circus, raising four children and

often traveling with her husband.

levels. He was born in Lowell, Massachusetts,

December 5, 1837 to Joseph and Susan Nichols Hall.

He was one of six children. Joseph and Susan Hall

moved to Wisconsin in 1859 and purchased a farm in

Magnolia.

Young George had his first taste of circus life at the

age of 10 and until his death in 1918, he never lost

his love for the business. According to the

Commemorative Biographical Record of Rock County,

published in 1909, "he would run away from home in

the spring, spend the summer with some circus, and

then return home in the fall to spend the winter at

home."

For a short time he worked in a candy factory in

Boston, then went to Concord and started selling

popcorn on the trains. In 1855, he went to New York

to sell popcorn. He made contact with Solon

Robinson, an editor of the New York Tribune.

Robinson had encouraged him to sell popcorn in New

York and after purchasing a supply of popcorn,

George became a popcorn vendor, also selling his

goods on the trains. Horace Greeley, another famous

New York Tribune editor, was credited with giving him

the name "Popcorn" Hall.

In March, 1855, at the age of 19, George Hall married

Sarah Wilder. Sarah shared her husband's

enthusiasm for the circus business. She was an active

participant in the circus, raising four children and

often traveling with her husband.

HALL FAMILY CIRCUS - FOUR GENERATIONS

EVANSVILLE, WISCONSIN

RESEARCHED AND WRITTEN BY RUTH ANN MONTGOMERY

EVANSVILLE, WISCONSIN

RESEARCHED AND WRITTEN BY RUTH ANN MONTGOMERY

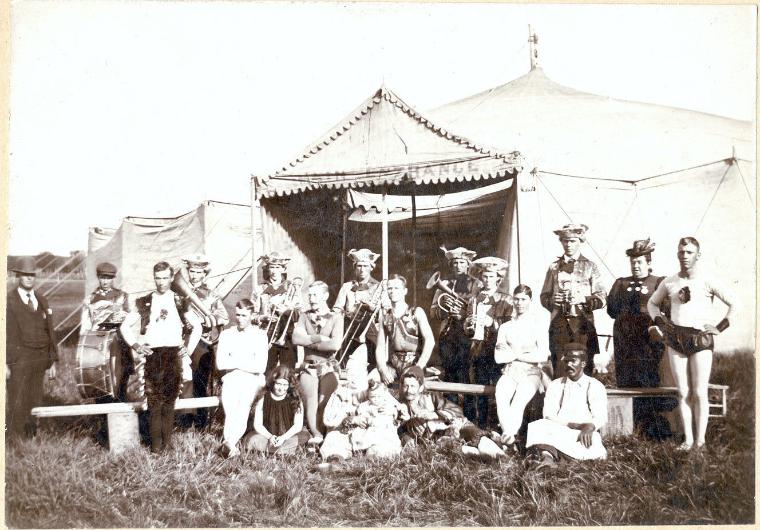

| Circus Performers from tintype |

Chapin's Champion Roman Hippodrome Asiatic Caravan and

Grand Golden Show, {owned by another local man whose first

name was never mentioned in the news articles) traveled with

Hall's Great California Exposition in the summer of 1874. Their

first show was on Friday, June 19, in Evansville. It was the first

Hall circus to be shown to Evansville audiences.

However, there were many years when Hall did not show in

Evansville. Other circus owners did not hesitate to compete with

the Hall Circus for the Evansville audiences. Adam Forepaugh

brought his "Four Mammoth Exhibitions" with four large tents to

Evansville in July 1872. Burr Robbins, whose show originated in

Janesville, held a circus in Evansville in 1875.

In 1876, George W. Hall married Marie Louise Tolen in St.

Louis, Missouri. They had one daughter, Mable, born in 1878.

George Hall's second wife, known as Lu, became an active part

of his circus as well.

Success in the circus business depended on mobility. George

Hall's circus traveled long distances over unpaved roads to find

an audience.

In November 1878, George Hall spent a short time in Evansville

to settle up some real estate dealings. Then he headed South

to catch up with his show that was in St. Louis, Missouri. From

Missouri, Hall intended to go to Texas. He had discovered that

in the winter months, he could keep the shows operating, by

moving to the Southern states.

Some years, he spent the entire winter season in the South. In

1879, he opened a museum in a store front on Main Street in

Memphis, Tennessee. He happened to be there on January 6,

1880, when a terrible fire in Memphis left one fireman dead.

George Hall's generous spirit came to front following the

disaster. He gave a benefit for the widow and children of Ed

Leonard, the fireman killed in the fire. The city of Memphis was

overwhelmed by his generosity and decided to give him a

medal.

Grand Golden Show, {owned by another local man whose first

name was never mentioned in the news articles) traveled with

Hall's Great California Exposition in the summer of 1874. Their

first show was on Friday, June 19, in Evansville. It was the first

Hall circus to be shown to Evansville audiences.

However, there were many years when Hall did not show in

Evansville. Other circus owners did not hesitate to compete with

the Hall Circus for the Evansville audiences. Adam Forepaugh

brought his "Four Mammoth Exhibitions" with four large tents to

Evansville in July 1872. Burr Robbins, whose show originated in

Janesville, held a circus in Evansville in 1875.

In 1876, George W. Hall married Marie Louise Tolen in St.

Louis, Missouri. They had one daughter, Mable, born in 1878.

George Hall's second wife, known as Lu, became an active part

of his circus as well.

Success in the circus business depended on mobility. George

Hall's circus traveled long distances over unpaved roads to find

an audience.

In November 1878, George Hall spent a short time in Evansville

to settle up some real estate dealings. Then he headed South

to catch up with his show that was in St. Louis, Missouri. From

Missouri, Hall intended to go to Texas. He had discovered that

in the winter months, he could keep the shows operating, by

moving to the Southern states.

Some years, he spent the entire winter season in the South. In

1879, he opened a museum in a store front on Main Street in

Memphis, Tennessee. He happened to be there on January 6,

1880, when a terrible fire in Memphis left one fireman dead.

George Hall's generous spirit came to front following the

disaster. He gave a benefit for the widow and children of Ed

Leonard, the fireman killed in the fire. The city of Memphis was

overwhelmed by his generosity and decided to give him a

medal.

Evansville Circus Parade, corner

of Main and Madison Streets

Central House Hotel in the

background

of Main and Madison Streets

Central House Hotel in the

background

Elephant crossing the intersection of

Madison and Main Streets, Evansville,

before 1898.

Click on photo to enlarge

Madison and Main Streets, Evansville,

before 1898.

Click on photo to enlarge

George "Popcorn" Hall believed to

be wearing the medal received for

his donations to the Memphis

fireman's family, after a fatal fire

be wearing the medal received for

his donations to the Memphis

fireman's family, after a fatal fire

An article about the ceremony was printed in the Memphis Public Ledger on February 2, 1880 and copied by the

Janesville Gazette on February 6, 1880. The medal was presented to George Hall by the fire chief "in recognition of the

bounteous sum he bestowed on the widow and children of the late fireman Ed Leonard." Hall would proudly wear the pin

for the rest of his life.

The medal was a gold eagle, suspended from a cross pin. The eagle was holding a wreath in its bill and inside the

Etruscan gold wreath was the inscription, "Presented to G. W. Hall by the fire department of Memphis, Tenn. for giving a

benefit in the aid of the widow and orphans of the fireman killed at the Main Street fire, January 6, 1880. Amount realized

$566.66. "Popcorn George".

At the ceremony, Popcorn George displayed his modesty and generosity. He also told a great deal about his work. To

the mayor of Memphis and the people of the city, Hall replied: "Gentlemen, I am not worthy of this high honor. The

people of your city put the money in my museum treasury for the very purpose you say I gave it. The part I played had

good return."

"Why a letter you gave me to the Mayor of New Orleans secured permission for my great moral entertainment to exhibit

free of charge in that great city until the first of April next. I haven't done a thing to deserve it. Never since the day I

began the struggle of life on my own account as a seller of popcorn on railway trains have I been so embarrassed as on

this occasion."

"I can stand in front of my museum and expatriate for hours upon the beauties of natural history; the animal species,

and the promotion of science through instruction received by all who visit my collection of curiosities, but I am not a

speech maker when it comes to a thing like this. Here Mr. Fire Chief, take this hundred dollar bill and use it for those

little children whose father lost his valuable life while earning a pittance to buy them bread."

Then George Hall handed the fire chief the hundred dollars. Several of those who listened to the speech and saw the

presentation, wiped tears from their eyes.

This was the first of many notices of Hall's generosity to the poor. He often gave benefit performances to support

organizations that gave to those less fortunate. Civil War veterans and orphans were always given free admission to his

shows.

Janesville Gazette on February 6, 1880. The medal was presented to George Hall by the fire chief "in recognition of the

bounteous sum he bestowed on the widow and children of the late fireman Ed Leonard." Hall would proudly wear the pin

for the rest of his life.

The medal was a gold eagle, suspended from a cross pin. The eagle was holding a wreath in its bill and inside the

Etruscan gold wreath was the inscription, "Presented to G. W. Hall by the fire department of Memphis, Tenn. for giving a

benefit in the aid of the widow and orphans of the fireman killed at the Main Street fire, January 6, 1880. Amount realized

$566.66. "Popcorn George".

At the ceremony, Popcorn George displayed his modesty and generosity. He also told a great deal about his work. To

the mayor of Memphis and the people of the city, Hall replied: "Gentlemen, I am not worthy of this high honor. The

people of your city put the money in my museum treasury for the very purpose you say I gave it. The part I played had

good return."

"Why a letter you gave me to the Mayor of New Orleans secured permission for my great moral entertainment to exhibit

free of charge in that great city until the first of April next. I haven't done a thing to deserve it. Never since the day I

began the struggle of life on my own account as a seller of popcorn on railway trains have I been so embarrassed as on

this occasion."

"I can stand in front of my museum and expatriate for hours upon the beauties of natural history; the animal species,

and the promotion of science through instruction received by all who visit my collection of curiosities, but I am not a

speech maker when it comes to a thing like this. Here Mr. Fire Chief, take this hundred dollar bill and use it for those

little children whose father lost his valuable life while earning a pittance to buy them bread."

Then George Hall handed the fire chief the hundred dollars. Several of those who listened to the speech and saw the

presentation, wiped tears from their eyes.

This was the first of many notices of Hall's generosity to the poor. He often gave benefit performances to support

organizations that gave to those less fortunate. Civil War veterans and orphans were always given free admission to his

shows.

Their oldest son, George, Jr. was born in 1857, a daughter, Ida, was born in Evansville in 1861. A second son,

Charles, was born in 1864 and a daughter, Jessie May in 1871. All of the children eventually entered the circus

business.

In 1860, George W. Hall joined the Dick-Sands wagon show. From New York, the circus followed the wagon

roads through Canada and what was then the West. The Sands show played in towns in Iowa, Illinois,

Minnesota and Wisconsin. That winter, Hall lived with his father on the farm in Magnolia.

In 1861, Hall went out with Jerry Mabie, a circus owner from Delavan, Wisconsin and the next year, Hall worked

with the George F. Bailey and the Van Amburg shows.

The winter of 1862-63, George Hall rented a storefront in Madison Wisconsin and opened a small museum. For

the next two years, Hall took his own show on the road in the summer.

His first spring on his own, Hall had to contend with a very rainy season. He headed for the lead mining region

in the southwest corner of the state. His operating expenses were $250 to $300 a day and when it rained, the

show business was slow. It was a short season for the new business. George Hall then put together a small side

show and traveled outside Wisconsin with Jim French's roundtop.

Hall once described the routine of the wagon show to a reporter: "we invariably had a 3 o'clock breakfast on

short rides, but if the drive to the next town we had billed was twenty-five or thirty miles we started away in the

evening as quick as we got through with our performance. All long trips were made by wagon trail."

Some towns were so small that there were no hotel

accommodations for the circus personnel. Then the

women and children were housed in the homes of the

villagers and the men slept under the wagons.

When the Hall troupe was not traveling with another

circus, or performing on their own, they made the

rounds of the county fairs. In the winter, the circus

disbanded and Hall would either rent a store for a

museum in a larger city or return to his father's home

in Magnolia. There he would trap animals and sell the

fur.

Putting a show together was an expensive

undertaking. Hall estimated that it had taken $10,000

to produce his first circus. Equipment, horse riders,

acrobats, clowns, and animals were all part of even

the smallest shows.

An August 1871 article in the Evansville Review gave

the salaries of circus performers. Those in the highest

salary ranges were with the larger circuses, including

P. T. Barnum's famous show. First class horse riders

could expect $100 a week, plus their traveling

expenses. "A good rider who has three or four smart

children or apprentices can make a very large salary."

Acrobats and clowns were paid from $20 to $150 per

week.

Barnum's show was traveling with 40 railroad cars

filled with circus people and paraphernalia in the early

1870s. The Evansville Review noted in 1872 that P. T.

Barnum's circus would show in the larger towns, such

as Janesville and Madison. Barnum estimated that it

cost $4,000 a day to operate his circus and they

needed a large audience to cover the expenses and

make a profit. The larger shows could not afford to

come to smaller communities.

The Evansville Review, February 11, 1874, reported

that Hall was making preparations to go into the show

business on a much larger scale than he had ever

done before. "Mr. Hall has all the energy and tack of a

showman; and his keen eye to business will ensure

him success in his favorite undertaking" the Review

reporter predicted.

Wagon shows, such as those owned in the early days

by George Hall, made the rounds of the smaller

towns. When Hall began putting his show together for

the 1874 season, he spent several months having his

carriages and cages repaired and painted and four

large tents were prepared for the traveling show. A

large of collection of "embalmed birds, embracing

many rare specimens" that had been on display in a

local jewelry store, was to be one of the major

attractions.

accommodations for the circus personnel. Then the

women and children were housed in the homes of the

villagers and the men slept under the wagons.

When the Hall troupe was not traveling with another

circus, or performing on their own, they made the

rounds of the county fairs. In the winter, the circus

disbanded and Hall would either rent a store for a

museum in a larger city or return to his father's home

in Magnolia. There he would trap animals and sell the

fur.

Putting a show together was an expensive

undertaking. Hall estimated that it had taken $10,000

to produce his first circus. Equipment, horse riders,

acrobats, clowns, and animals were all part of even

the smallest shows.

An August 1871 article in the Evansville Review gave

the salaries of circus performers. Those in the highest

salary ranges were with the larger circuses, including

P. T. Barnum's famous show. First class horse riders

could expect $100 a week, plus their traveling

expenses. "A good rider who has three or four smart

children or apprentices can make a very large salary."

Acrobats and clowns were paid from $20 to $150 per

week.

Barnum's show was traveling with 40 railroad cars

filled with circus people and paraphernalia in the early

1870s. The Evansville Review noted in 1872 that P. T.

Barnum's circus would show in the larger towns, such

as Janesville and Madison. Barnum estimated that it

cost $4,000 a day to operate his circus and they

needed a large audience to cover the expenses and

make a profit. The larger shows could not afford to

come to smaller communities.

The Evansville Review, February 11, 1874, reported

that Hall was making preparations to go into the show

business on a much larger scale than he had ever

done before. "Mr. Hall has all the energy and tack of a

showman; and his keen eye to business will ensure

him success in his favorite undertaking" the Review

reporter predicted.

Wagon shows, such as those owned in the early days

by George Hall, made the rounds of the smaller

towns. When Hall began putting his show together for

the 1874 season, he spent several months having his

carriages and cages repaired and painted and four

large tents were prepared for the traveling show. A

large of collection of "embalmed birds, embracing

many rare specimens" that had been on display in a

local jewelry store, was to be one of the major

attractions.

In the 1880s, the Hall family purchased property

near Evansville and made its winter headquarters in

Wisconsin. George Hall Jr. purchased 20 acres of

land in Section 34 of Union township from L. H.

Walker for $1,250. This became the headquarters

of the Hall Circus at the south end of what is today

First Street.

Animals in the Hall circus included a trained hog

named Charley. Hall claimed he had shown the

animal to more than 400,000 people. When it

became too old to perform, the animal was sold to

the firm of Smith & Eager, a general store and

grocery owned by Almeron Eager and William

Smith. What the store owners did with the trained

pig was never reported.

A mountain lion was one of the larger animals in the

circus. The cat had come from Texas and

measured seven feet from head to tail. Another

curiosity was a gander that could perform card

tricks. Monkeys and lions were also part of the

show.

The farm was a working farm, as well as a circus

headquarters. When tobacco became a popular

cash crop, George Hall was one of the first to begin

raising it. He also had livestock and announced

sales of pure-bred stock on his farm in a November

1882 ad in the Evansville Review.

Hall, also began to accumulate real estate in the

village of Evansville. In 1882, he purchased land to

build a boarding house near the Seminary. The

Evansville Review predicted that "Mr. Hall will

always have his building profitably occupied."

near Evansville and made its winter headquarters in

Wisconsin. George Hall Jr. purchased 20 acres of

land in Section 34 of Union township from L. H.

Walker for $1,250. This became the headquarters

of the Hall Circus at the south end of what is today

First Street.

Animals in the Hall circus included a trained hog

named Charley. Hall claimed he had shown the

animal to more than 400,000 people. When it

became too old to perform, the animal was sold to

the firm of Smith & Eager, a general store and

grocery owned by Almeron Eager and William

Smith. What the store owners did with the trained

pig was never reported.

A mountain lion was one of the larger animals in the

circus. The cat had come from Texas and

measured seven feet from head to tail. Another

curiosity was a gander that could perform card

tricks. Monkeys and lions were also part of the

show.

The farm was a working farm, as well as a circus

headquarters. When tobacco became a popular

cash crop, George Hall was one of the first to begin

raising it. He also had livestock and announced

sales of pure-bred stock on his farm in a November

1882 ad in the Evansville Review.

Hall, also began to accumulate real estate in the

village of Evansville. In 1882, he purchased land to

build a boarding house near the Seminary. The

Evansville Review predicted that "Mr. Hall will

always have his building profitably occupied."

George W. Hall farm with barns for circus animals

and paraphernalia. The farm was located in Union

township at the south end of South First Street in

Evansville.

and paraphernalia. The farm was located in Union

township at the south end of South First Street in

Evansville.

Most people knew the Hall family for their circus work. Preparation for the summer season began in the early spring.

Wagons were built, painted, and cleaned for the coming season.

People were hired to go with the show. In April 1883, a former Evansville Review printer, C. N. Wells, joined the Hall

circus as a clown. When the show was ready for the season, Hall had decided that there were already too many

circuses headquartered in Wisconsin and he decided to take his circus to the south to join the George DeHaven

show.

In 1884, Hall went to New York to purchase some exotic animals from one of the shows he had followed. The Van

Amburg menagerie auction sale was held in March 1884 and George Hall purchased 10 to 12 thousand dollars

worth of animals, including two Egyptian camels, two African dromedaries, an East India elephant and a South

American jaguar.

The animals were included when his show went on the road the following summer. His acts also included Charles

and Viola Lane, a husband and wife team of trapeze artists. The Hall Circus was booked for engagements in Eau

Claire, Elroy, Stoughton and Brodhead in the summer of 1884.

While performing in Eau Claire, the Lanes had a terrible accident. The Lanes' trapeze had been suspended 20 feet

into the air. Charles Lane was swinging from the trapeze and reaching out for Viola Lane when the support poles

gave way and the performers came crashing down to the ground.

The gas lights that hung from the center pole also came down, spilling gasoline on the performers, and the ground.

Flames from the gas lights spread across the dirt floor, nearly reaching the canvas of the tent.

The audience began to rush for the exits. Amid the excitement, some members of the audience and the circus crew

had the presence of mind to try to extinguish the fire before it reached the side walls of the tent.

The impromptu rescuers threw sand on the fire. Others helped the Lanes escape from the flames. A serious

disaster was averted and the Lanes were shaken, but suffered no permanent injuries.

Hall became more adventurous in his travels with the circus. The following year, Hall once again joined up with

George DeHaven's Circus. In the winter of 1884-85 the Hall and George DeHaven circuses rented a ship and

traveled to the Caribbean Islands. All of their tents, equipment, animal cages and personnel went by ship.

George Hall's second wife, Mary Louise Hall, wrote a letter to her mother from St. Pierre Island of Martinique on

January 26, 1885. The letter was published in the February 17, 1885 Evansville Review.

According to Lu Hall's report, the Hall circus had played for four days at St. Johns in Antiqua. There were no horses

on the island and to get the circus to its location on the island, all of the items had to be transported by carts, drawn

by men who lived on the island. The carts were so small that only one animal cage would fit in a cart.

While the animals were being transported on the small carts, one of the islanders became curious about the animals

and opened one of the bear cages. The bear escaped and panic broke out. The islanders were so frightened that

they never attempted to open another cage. After the fiasco with the bear, the trainers decided that the elephant

would be brought ashore at night.

Wagons were built, painted, and cleaned for the coming season.

People were hired to go with the show. In April 1883, a former Evansville Review printer, C. N. Wells, joined the Hall

circus as a clown. When the show was ready for the season, Hall had decided that there were already too many

circuses headquartered in Wisconsin and he decided to take his circus to the south to join the George DeHaven

show.

In 1884, Hall went to New York to purchase some exotic animals from one of the shows he had followed. The Van

Amburg menagerie auction sale was held in March 1884 and George Hall purchased 10 to 12 thousand dollars

worth of animals, including two Egyptian camels, two African dromedaries, an East India elephant and a South

American jaguar.

The animals were included when his show went on the road the following summer. His acts also included Charles

and Viola Lane, a husband and wife team of trapeze artists. The Hall Circus was booked for engagements in Eau

Claire, Elroy, Stoughton and Brodhead in the summer of 1884.

While performing in Eau Claire, the Lanes had a terrible accident. The Lanes' trapeze had been suspended 20 feet

into the air. Charles Lane was swinging from the trapeze and reaching out for Viola Lane when the support poles

gave way and the performers came crashing down to the ground.

The gas lights that hung from the center pole also came down, spilling gasoline on the performers, and the ground.

Flames from the gas lights spread across the dirt floor, nearly reaching the canvas of the tent.

The audience began to rush for the exits. Amid the excitement, some members of the audience and the circus crew

had the presence of mind to try to extinguish the fire before it reached the side walls of the tent.

The impromptu rescuers threw sand on the fire. Others helped the Lanes escape from the flames. A serious

disaster was averted and the Lanes were shaken, but suffered no permanent injuries.

Hall became more adventurous in his travels with the circus. The following year, Hall once again joined up with

George DeHaven's Circus. In the winter of 1884-85 the Hall and George DeHaven circuses rented a ship and

traveled to the Caribbean Islands. All of their tents, equipment, animal cages and personnel went by ship.

George Hall's second wife, Mary Louise Hall, wrote a letter to her mother from St. Pierre Island of Martinique on

January 26, 1885. The letter was published in the February 17, 1885 Evansville Review.

According to Lu Hall's report, the Hall circus had played for four days at St. Johns in Antiqua. There were no horses

on the island and to get the circus to its location on the island, all of the items had to be transported by carts, drawn

by men who lived on the island. The carts were so small that only one animal cage would fit in a cart.

While the animals were being transported on the small carts, one of the islanders became curious about the animals

and opened one of the bear cages. The bear escaped and panic broke out. The islanders were so frightened that

they never attempted to open another cage. After the fiasco with the bear, the trainers decided that the elephant

would be brought ashore at night.

Article from the February 17 1885,

Enterprise, p. 4, col. 3, Evansville,

Wisconsin

Enterprise, p. 4, col. 3, Evansville,

Wisconsin

In the summer of 1885, the Hall shows were in Chicago. The following December, George Hall was traveling in

Mexico with his circus.

He had planned to spend the winter in Galveston, Texas, but a large fire destroyed the area he had intended to use

for setting up the circus. When the fire was raging, Hall moved his circus five times to escape the flames.

From Galveston the Halls went to Nuevo Laredo and crossed the border into Mexico. They arrived in Monterey,

Mexico and the company found itself in the midst of a civil war. They stayed for eight days and Hall telegraphed to

Mexican President Diaz to send troops to protect the Americans.

Diaz complied and sent troops to protect the Hall circus. Hall told the reporter for the Evansville Enterprise that the

"excitement kills the show business." He had seen five men killed and ten or twelve wounded, during his travels in

Mexico.

Not wanting to give up the business in Mexico, Hall moved his circus by railroad across 400 miles of Mexico. He

showed in cities from Zacatecas to the City of Mexico, then came back to the United States the following spring.

Some of his circus personnel had been sick with small pox and many of the towns in New Mexico and Colorado

quarantined the show and would not let the Hall circus perform. Hall decided to close the show and shipped it home

to Evansville.

By 1887, Hall seemed to have decided on a quieter life. He sold his show to George D. Haven for $10,000. Not

wanting to give up the show business entirely, George Hall kept an Arabian dromedary, and a few other animals.

That winter he spent most of his leisure time trapping mink, along the streams of Allens Creek. After he trapped the

animals, he tanned their pelts and had the furs made into clothing for himself and his family. It was only a temporary

rest from the circus business.

What made the Hall circuses successful was George W. Hall, Sr.'s ability to be creative in the face of adversity. He

had the foresight and financial ability to purchase circus animals and property, that others avoided.

His gregarious personality put him in contact with many others in the show business. This allowed Hall to learn trade

show secrets and to be in touch with the economic forecast for the success of circuses in various parts of the

country. When one area of the country was in economic decline and the fortunes of the circus business seemed low,

Hall would change the location to what would seem to be a more profitable location.

George Washington "Popcorn" Hall set up his show tents in Evansville in October 1887. He opened his show on a

Saturday and showed a collection of Mexican "curiosities" which included Navajo blankets, Mexican lace, Indian war

clubs and other items he had collected as souvenirs during his Mexican journeys. Hall also had on display some rare

tropical birds and an "educated pig and gander". The cost of the show was 10 cents.

While his family performed in various acts, including tumbling and daring fetes on the trapeze, "Pop" Hall explained

the various animals that he had on exhibit in the menagerie. The Evansville Review reporter noted that "Mr. Hall,

possesses a genius in that line and manifested an apparent delight in doing so".

Although the show had not been as well attended as it could have been, the proceeds of the program were

twenty-two dollars. Hall donated his time and that of his performers so that all of the money could be used to

purchase food for those in need. Hall used the receipts to purchase 23 sacks of flour which he personally delivered

to poor families in the village.

The winter of 1887-88, the Hall family remained in Evansville and "Pop" Hall's energies were devoted to farming. He

advertised "rice popcorn" for sale and mentioned that it was especially good for old people, because the kernels

"popped up so tender". Hall also reported the first hatch of chicks in Evansville in January 1888.

The oldest son, George Hall, Jr., was already beginning to collect animals to form his own show. He had at least one

alligator and when it died, the carcass was given to William Campbell.

William and his father, Byron Campbell also collected curiosities and had enough to open a museum themselves.

The Campbells had the alligator stuffed and mounted and put it on display in the Campbell & Sons meat market.

Mexico with his circus.

He had planned to spend the winter in Galveston, Texas, but a large fire destroyed the area he had intended to use

for setting up the circus. When the fire was raging, Hall moved his circus five times to escape the flames.

From Galveston the Halls went to Nuevo Laredo and crossed the border into Mexico. They arrived in Monterey,

Mexico and the company found itself in the midst of a civil war. They stayed for eight days and Hall telegraphed to

Mexican President Diaz to send troops to protect the Americans.

Diaz complied and sent troops to protect the Hall circus. Hall told the reporter for the Evansville Enterprise that the

"excitement kills the show business." He had seen five men killed and ten or twelve wounded, during his travels in

Mexico.

Not wanting to give up the business in Mexico, Hall moved his circus by railroad across 400 miles of Mexico. He

showed in cities from Zacatecas to the City of Mexico, then came back to the United States the following spring.

Some of his circus personnel had been sick with small pox and many of the towns in New Mexico and Colorado

quarantined the show and would not let the Hall circus perform. Hall decided to close the show and shipped it home

to Evansville.

By 1887, Hall seemed to have decided on a quieter life. He sold his show to George D. Haven for $10,000. Not

wanting to give up the show business entirely, George Hall kept an Arabian dromedary, and a few other animals.

That winter he spent most of his leisure time trapping mink, along the streams of Allens Creek. After he trapped the

animals, he tanned their pelts and had the furs made into clothing for himself and his family. It was only a temporary

rest from the circus business.

What made the Hall circuses successful was George W. Hall, Sr.'s ability to be creative in the face of adversity. He

had the foresight and financial ability to purchase circus animals and property, that others avoided.

His gregarious personality put him in contact with many others in the show business. This allowed Hall to learn trade

show secrets and to be in touch with the economic forecast for the success of circuses in various parts of the

country. When one area of the country was in economic decline and the fortunes of the circus business seemed low,

Hall would change the location to what would seem to be a more profitable location.

George Washington "Popcorn" Hall set up his show tents in Evansville in October 1887. He opened his show on a

Saturday and showed a collection of Mexican "curiosities" which included Navajo blankets, Mexican lace, Indian war

clubs and other items he had collected as souvenirs during his Mexican journeys. Hall also had on display some rare

tropical birds and an "educated pig and gander". The cost of the show was 10 cents.

While his family performed in various acts, including tumbling and daring fetes on the trapeze, "Pop" Hall explained

the various animals that he had on exhibit in the menagerie. The Evansville Review reporter noted that "Mr. Hall,

possesses a genius in that line and manifested an apparent delight in doing so".

Although the show had not been as well attended as it could have been, the proceeds of the program were

twenty-two dollars. Hall donated his time and that of his performers so that all of the money could be used to

purchase food for those in need. Hall used the receipts to purchase 23 sacks of flour which he personally delivered

to poor families in the village.

The winter of 1887-88, the Hall family remained in Evansville and "Pop" Hall's energies were devoted to farming. He

advertised "rice popcorn" for sale and mentioned that it was especially good for old people, because the kernels

"popped up so tender". Hall also reported the first hatch of chicks in Evansville in January 1888.

The oldest son, George Hall, Jr., was already beginning to collect animals to form his own show. He had at least one

alligator and when it died, the carcass was given to William Campbell.

William and his father, Byron Campbell also collected curiosities and had enough to open a museum themselves.

The Campbells had the alligator stuffed and mounted and put it on display in the Campbell & Sons meat market.

Lida and Grace

Hall

Hall

A third generation of circus performers and owners was born to the Hall family in the 1880s. George Hall, Jr. married

Lida Ward in 1882 at Dubuque, Iowa. Their first son, Frank was born in December 23, 1883. On March 28, 1886, their

daughter, Grace, was born and on March 19, 1897, their son, Charles Russell, was born. The children began traveling

with their parents' circus at a very early age.

By 1888, two Hall circuses were headquartered in Evansville. With two George Hall circuses on the road, newspaper

reporters added "Pop", "Popcorn" or "Col." to George Hall Sr.'s name to distinguish the father and son.

The Evansville Tribune reported that George Hall, Jr. had started out for Ohio with his show in April 1888. In June of that

same year, Col. George "Popcorn" Hall set up his tents at the corner of Root and Wallace Streets in Chicago. One of

the Chicago daily newspapers gave "Pop" Hall rave reviews.

Goodall's Daily Sun, a Chicago paper, reported that Hall had "one of the best and certainly the largest of all the cheap

price shows that have ever visited Chicago and vicinity." This was a return visit as Hall had his set his circus tents on the

same lot in 1883.

The Daily Sun gave "Pop" Hall credit for originating the 10 cent admission charge for circuses. The Sun went on to

report that Hall's show had "large circus tents that will hold 10,000 people and the menagerie is a well selected one

embracing many of the choicest and most costly animals." The Bingley's Royal European Menagerie had recently been

purchased by Hall, increasing the size of the animal acts. The newspaper reporter promised the Daily Sun's readers that

Hall's thirty acts would be immensely entertaining.

"Pop" Hall spent the winter of 1888-89 in the south. During the fall election of 1888, he was in Memphis, Tennessee and

got into trouble with the federal authorities when he was falsely accused of illegal voting and intimidation at the polls. Hall

was arrested in Little Rock and taken back to Memphis to be put in jail.

When the Federal marshals and Hall arrived in Memphis, Hall contacted the city fire chief. The chief remembered Hall's

generosity to the fireman's widow and children after the deadly fire in 1880 and set to work immediately to post bail for

the generous circus owner. There were several Memphis cotton merchants who posted a $10,000 bond for Hall's

release.

Pop Hall returned to his show and continued on through the south until April 1889, when the troupe returned to

Evansville. For a few months, Col. Hall concentrated on his farm and once again raised a crop of rice popcorn.

In July, he offered 500 bushels of rice popcorn for sale at $1 a bushel. That same month he also advertised that he

wanted to buy 100 "cheap horses that will stand the road". He was about to take his show on the road once again.

This time he took Sam McFlynn as his partner. McFlynn had trained horses and dogs. The Hall-McFlynn circus gave a

performance in Evansville in August 1889 and announced they were heading south for the winter. The trip was

interrupted by the legal proceedings involving Hall and the federal government.

In the early winter of 1890, the charge of the illegal voting against Hall was brought to the Federal courts. Such

prominent Evansville men as Nelson Winston, former banker and general store owner; Matt Broderick, livery stable

owner; C. E. Lee, harness maker; and James V. Sonn, pharmacist, were called to testify in the U. S. Supreme Court in

Memphis on behalf of Col. Hall. In February 1890, Hall was acquitted of all charges. The trial resulting from the false

accusations had cost him nearly $5,000, but he was free.

In the spring of 1890, George Hall, Jr. was ready to set out from Evansville with his show once again. In April 1890, he

loaded a railroad car filled with show stock and shipped it to Warrenburg, Missouri. There he joined the Whitting

Brothers Show.

After spending the early spring and summer on the road, George, Jr. returned to Evansville. He had replaced the

alligator that had ended up as a display in Campbell's meat market and while he was home, the water-loving creature

escaped from its cage.

The July 8, 1890 Evansville Tribune announced that Hall's alligator "is now roaming at large in our village. He would be a

dangerous animal to meet especially by children."

Many people thought the animal would be found in the mill pond, a favorite swimming place for young boys. However, it

was discovered in the marsh, south of the village. To capture the animal, a fence board was crammed into its mouth and

a chain was put around its neck. The alligator was led back to Hall's farm and once again confined to its cage.

Lida Ward in 1882 at Dubuque, Iowa. Their first son, Frank was born in December 23, 1883. On March 28, 1886, their

daughter, Grace, was born and on March 19, 1897, their son, Charles Russell, was born. The children began traveling

with their parents' circus at a very early age.

By 1888, two Hall circuses were headquartered in Evansville. With two George Hall circuses on the road, newspaper

reporters added "Pop", "Popcorn" or "Col." to George Hall Sr.'s name to distinguish the father and son.

The Evansville Tribune reported that George Hall, Jr. had started out for Ohio with his show in April 1888. In June of that

same year, Col. George "Popcorn" Hall set up his tents at the corner of Root and Wallace Streets in Chicago. One of

the Chicago daily newspapers gave "Pop" Hall rave reviews.

Goodall's Daily Sun, a Chicago paper, reported that Hall had "one of the best and certainly the largest of all the cheap

price shows that have ever visited Chicago and vicinity." This was a return visit as Hall had his set his circus tents on the

same lot in 1883.

The Daily Sun gave "Pop" Hall credit for originating the 10 cent admission charge for circuses. The Sun went on to

report that Hall's show had "large circus tents that will hold 10,000 people and the menagerie is a well selected one

embracing many of the choicest and most costly animals." The Bingley's Royal European Menagerie had recently been

purchased by Hall, increasing the size of the animal acts. The newspaper reporter promised the Daily Sun's readers that

Hall's thirty acts would be immensely entertaining.

"Pop" Hall spent the winter of 1888-89 in the south. During the fall election of 1888, he was in Memphis, Tennessee and

got into trouble with the federal authorities when he was falsely accused of illegal voting and intimidation at the polls. Hall

was arrested in Little Rock and taken back to Memphis to be put in jail.

When the Federal marshals and Hall arrived in Memphis, Hall contacted the city fire chief. The chief remembered Hall's

generosity to the fireman's widow and children after the deadly fire in 1880 and set to work immediately to post bail for

the generous circus owner. There were several Memphis cotton merchants who posted a $10,000 bond for Hall's

release.

Pop Hall returned to his show and continued on through the south until April 1889, when the troupe returned to

Evansville. For a few months, Col. Hall concentrated on his farm and once again raised a crop of rice popcorn.

In July, he offered 500 bushels of rice popcorn for sale at $1 a bushel. That same month he also advertised that he

wanted to buy 100 "cheap horses that will stand the road". He was about to take his show on the road once again.

This time he took Sam McFlynn as his partner. McFlynn had trained horses and dogs. The Hall-McFlynn circus gave a

performance in Evansville in August 1889 and announced they were heading south for the winter. The trip was

interrupted by the legal proceedings involving Hall and the federal government.

In the early winter of 1890, the charge of the illegal voting against Hall was brought to the Federal courts. Such

prominent Evansville men as Nelson Winston, former banker and general store owner; Matt Broderick, livery stable

owner; C. E. Lee, harness maker; and James V. Sonn, pharmacist, were called to testify in the U. S. Supreme Court in

Memphis on behalf of Col. Hall. In February 1890, Hall was acquitted of all charges. The trial resulting from the false

accusations had cost him nearly $5,000, but he was free.

In the spring of 1890, George Hall, Jr. was ready to set out from Evansville with his show once again. In April 1890, he

loaded a railroad car filled with show stock and shipped it to Warrenburg, Missouri. There he joined the Whitting

Brothers Show.

After spending the early spring and summer on the road, George, Jr. returned to Evansville. He had replaced the

alligator that had ended up as a display in Campbell's meat market and while he was home, the water-loving creature

escaped from its cage.

The July 8, 1890 Evansville Tribune announced that Hall's alligator "is now roaming at large in our village. He would be a

dangerous animal to meet especially by children."

Many people thought the animal would be found in the mill pond, a favorite swimming place for young boys. However, it

was discovered in the marsh, south of the village. To capture the animal, a fence board was crammed into its mouth and

a chain was put around its neck. The alligator was led back to Hall's farm and once again confined to its cage.

In October, George Hall, Jr. and his son, seven-year-old

son, Frankie, went to join the Cole and Middleton's

circuses in Chicago. They took along their trained pig,

goose and snakes. Like his father, George, Jr. was

always on the look-out for different animals and

performers.

In February 1891, George, Jr. purchased more circus

paraphernalia from the Ringling Brothers circuses

headquartered in Baraboo. He made plans to go on the

road in the spring.

While his oldest son was working with shows in the

north, George Hall, Sr. moved south and was showing in

Galveston, Liberty and Beaumont Texas in March of

1891. He returned to Evansville in April and offered his

son, Charles, a start in the circus business. George Sr.'s

daughter, Jessie, who had married to another circus

performer, Frank McCart, traveled with Charles' show.

"Pop" Hall, the McCarts and Charles organized a "Grand

Railroad Show" and the new circus gave its first show in

Evansville in May. They rented Dr. Evan's pasture, north

of the Evans home on West Main Street.

son, Frankie, went to join the Cole and Middleton's

circuses in Chicago. They took along their trained pig,

goose and snakes. Like his father, George, Jr. was

always on the look-out for different animals and

performers.

In February 1891, George, Jr. purchased more circus

paraphernalia from the Ringling Brothers circuses

headquartered in Baraboo. He made plans to go on the

road in the spring.

While his oldest son was working with shows in the

north, George Hall, Sr. moved south and was showing in

Galveston, Liberty and Beaumont Texas in March of

1891. He returned to Evansville in April and offered his

son, Charles, a start in the circus business. George Sr.'s

daughter, Jessie, who had married to another circus

performer, Frank McCart, traveled with Charles' show.

"Pop" Hall, the McCarts and Charles organized a "Grand

Railroad Show" and the new circus gave its first show in

Evansville in May. They rented Dr. Evan's pasture, north

of the Evans home on West Main Street.

| Geo. W. Hall's Animal Show - 1900 |

The circus band led the street parade to the grounds where the show was to be held. The program opened with

a horizontal bar trapeze act and a tumbling act. Jessie's husband, Frank McCart, performed juggling and trapeze

acts.

Following its opening show in Evansville, the show went on the road. In June, the circus had traveled across the

prairies and reached Wyoming where a private "pleasure garden" leased the show.

That August, Col. Hall returned home to Evansville so he could begin preparing for another southern tour.

According to a Janesville Gazette report, the trip would include the Caribbean islands he had visited six year

earlier.

"Pop" Hall hired local wagon maker, Joel W. Morgan, to repair cages. Caleb Lee made new harnesses for the

horses and George Backenstoe was busy painting wagons and cages. The troupe would travel by four railroad

cars. Backenstoe was also hired to paint the railroad cars before the show turned south.

While the preparations for the southern tour were taking place, " Pop" Hall heard of a large sale of wild animals.

Always looking for new exhibits for his menagerie, Hall went to St. Louis in early August 1891 for large sale of

animals. He made several purchases and a few weeks later cages of wild animals arrived at the Evansville depot.

The purchases included two lions and a elk. He had also purchased a Brahma cow, which he billed to his circus

audiences as the sacred cow of India.

In September, the Evansville Tribune reported that "Our town is full of showmen and show fixtures preparing for

the departure of Hall's great combination shows." Hall, his son, Charles, and the Sam McFlynn Show had joined

forces for the winter.

Once again, Col. George Washington Hall displayed his generous spirit to the people of Evansville. The

Hall-McFlynn Circus gave two performances in Evansville and the proceeds from the first day were given to build

a band stand near the Central House. The second day's proceeds were given for the relief of the poor people in

Evansville.

The winter of 1891-92, the Hall shows played in Florida cities, including Tampa and Jacksonville. George Hall

sent orange blossoms and palmettos to his friends in the North. Almeron Eager, who often acted as his financial

agent, reported that the Halls had purchased more than $5,000 worth of cars, camels and show animals, and

they expected to purchase an elephant.

The combined shows were enjoying great success in Florida. Proceeds from their programs were ample to take

care of the expenses and to purchase the new equipment. "This success of Messrs. Hall is not only gratifying to

themselves, but quite as much so to their many friends at home.", a Review reporter noted in February 1892.

In the spring, the Halls returned to Evansville, to organize their shows for northern tours in the summer. All of the

children by Col. Hall's first wife were out on the road when they received word that their mother had died.

Sarah Wilder Hall had remarried following her divorce from "Pop" Hall in the 1870s. She was living in Kansas City,

Missouri at the time of her death.

Accompanied by her two daughters and their husbands, the body of Sarah H. Wilder Hall Pettengill was brought

back to Evansville for burial. The obituary notice in the September 20, 1892 Tribune told of the arrival of Sarah's

children for her funeral. Daughters Ida and Jessie were in Kansas City, Missouri with their husbands, Tod Blair

and Frank McCart.

George, Jr. was in Dubuque, Iowa and he sent his wife, Lida, to represent him at the funeral. Charles' shows

were playing in Oklahoma and he also arrived by train in time for his mother's funeral. She was buried in the

cemetery plot purchased by her son, George Jr..

Tragedy would fill the lives of Col. Hall and his children during the next few years. His daughter, Ida, had "Brights'

Disease", an inflammation of the kidneys, also called nephritis. In June 1894, Hall persuaded Ida to go to a

Chicago hospital for treatment. Her father and husband accompanied her to Chicago. Within a short while she

returned home. The newspaper announcement of her arrival noted that "she received but little help or

encouragement and is still suffering greatly from Bright's disease."

After his attempts to get treatment for Ida, "Pop" Hall returned to his show in the east. While the Hall show was in

Cincinnati, "Pop" Hall heard that a circus owned by a man named Davis was in financial trouble.

Hall contacted Davis and offered to purchase the entire show. Davis agreed and offered to include an elephant

named Empress that was leased from the Empire Printing Company of Chicago. Hall took charge of the elephant,

as well as the other circus goods.

One evening, Hall was feeding his own elephants, when Empress became jealous and attacked Hall. The animal

knocked him down with her trunk. The fall had knocked Hall unconscious and before help arrived, Empress

pressed Col. Hall into the ground, breaking his right hip. Rescuers finally arrived and took the injured man to a

hospital.

Hall was fearless and optimistic about the elephant, even if it had attacked him. He contacted the Empire Printing

Company while he was still in the hospital recovering from his injuries. The owners agreed to sell Col. Hall the

elephant for $1,000. In return, Hall promised he would not sue Empire Printing for damages. Hall's gain was a

rogue elephant that he could not tame. He sold Empress in the summer of 1895 for $2,000.

While Col. Hall was bed-ridden with the broken hip a second tragedy occurred. His daughter, Ida, died on July 9,

1894, at the age of thirty three. Her funeral was held in Evansville and because of his injuries, Hall could not

attend. Ida's brother George, was out with his show, and could also not attend the funeral.

The winter of 1894, Hall returned to Florida. The previous January he had purchased two acres of land in Tampa

and told the Tampa Times newspaper that he intended to make that his winter headquarters. The Tampa Times

reported that he intended to fence the property, build houses for his actors and stables for the horses and other

circus animals.

"Pop" Hall's circus animals arrived back in Evansville in April 1895. The animals were led from the depot to Hall's

farm. When one of the camels passed by a horse that was hitched to a post beside the street, the horse

collapsed and died of fright.

In May, two different Hall circuses once again left Evansville. Col. Hall announced that he planned to retire and

his son, Charles, would run a railroad show, while his son, George would operate a wagon show. It was the first of

several notices over the next few years, that the elder Hall would give up the show business.

George Hall, Jr. announced in April 1895 that he had purchased his father's show animals. The new show was

billed as "Geo. W. Hall Jr. Great Trained Animal Show Museum and Menagerie" and an Evansville Tribune ad

announced that the first exhibit would be in Evansville on May 4, 1895.

The younger Hall advertised that his show included his father's elephants, camels and other animals. George,

Jr.'s menagerie included the only living gorilla in America, three performing elephants, including Queen, Empress

and Palm, and 16 cages of other animals.

Hall's brother-in-law, Frank McCart performed as the slack wire walker and as an acrobat and clown. A Prof.

Showers, with his two young daughters, who were horseback riders and trapeze performers were also with the

show. When they left Evansville the show's name had changed to the Hall & Showers circus.

The following winter, in early February, 1896, Charles Hall was traveling with his circus in the southern states. He

had stopped his show in Meridian, Mississippi and was too sick with pneumonia to continue. His father was

notified by telegram that Charles was critically ill and went immediately to see him. However, Charles died before

his father arrived.

Col. George W. Hall accompanied his son's body back to Evansville. Charles' body was prepared for burial and

taken to the Hall home at the south edge of Evansville. A large funeral procession led by Evansville's Black

Hussar Band marched from the Hall farm to the Methodist Church on South Madison Street.

The church was nearly filled with young men who came to pay their final respects to Charles. The Methodist choir

sang several selections and Rev. G. W. White preached from the text "So teach us to number our days that we

may apply our hearts unto wisdom."

Following the service, the Black Hussar Band then escorted the grieving family and friends to Maple Hill

Cemetery. There Charles was buried beside his mother and sister, Ida.

Despite the tragedies that befell his family, Col. Hall, who was now 59 years old, came out of retirement to

reorganize Charles' circus. He could not resist the call of the road, he once told a reporter.

In March 1896, the Evansville newspapers reported that Col. Hall was going to take his circus by railroad to

California and Mexico. He would be traveling once again with Sam McFlynn and "educated ponies", dogs, bears,

deer, goats, and monkeys would be with the show.

Col. G. W. Hall's menagerie, which he had reacquired from his son, George, included the elephant "Queen" and

her baby "Palm", a baby camel. A "man eating" lion, named Nero, was also with the show. The show was billed as

the "Hall and McFlynn New United States Shows".

They gave their first showing in May in Evansville. McFlynn's Japanese pony "Metoo" was in training to make a

75 foot slide down a wire that ran diagonally from the top of the circus tent to the ground. There was to be a

street parade, balloon ascension and trapeze act before the show began.

Hall and McFlynn had hired an advertising agent to go ahead of their show to advertise the circus' arrival in a

city. The show's general agent, Thomas R. Perry, traveled several days ahead of the show date. Perry had his

own advance railroad car that carried about ten people, including five people to bill posters, a press agent, and

other advertising personnel.

Though he was crippled and in ill health, Col. George W. Hall, once again answered the call of the circus ring

and headed out with his "mammoth railroad show".

In the late 1890s, both Col. George Washington Hall and his son George W. Hall, Jr. were on the road with

circuses. For over two years, from the summer of 1896 to September 1898, Col. Hall and his partner, Sam

McFlynn, traveled in the southern United States and Mexico with a railroad show.

During much of the time, his daughter Jessie and her husband, Frank McCart traveled with them. Also in the

company were Pop Hall's wife, Lou, and their daughter, Mable.

The George W. Hall, Jr. show stayed closer to home and followed a circus route in the late spring and summer

and the county fair circuit in the fall. In early August 1896, George, Jr. arrived in Evansville, packed away his

circus property and reorganized his "fairground show" for the fall season.

George, Jr. advertised that he wanted to purchase 50 tons of hay and straw and one thousand bushes of oats

and corn to feed his animals through the winter months. Circus historians believe that the availability of food for

the circus animals is one reason Wisconsin was home to so many small circuses.

When the fair season was finished, George, Jr. returned to Evansville. In November 1896, George, Jr. purchased

40 acres of land in the northwest corner of section 22 in Union township. It was located just north of Evansville at

the end of what is today Elmer Road.

He bought the land from local banker, George L. Pullen for $1,600 and George Hall, Jr. used this property as the

winter headquarters for his circus.

During this same time, the circus operated by Col. George Hall and Sam McFlynn traveled by railroad through

the southern states and Mexico. The Hall & McFlynn Circus had fifty trained ponies, dogs, bears, monkeys and

the elephants Queen and her baby, Palm. Occasional news articles appeared over the next two years

concerning Col. Hall and his circus, but it was George Hall, Jr. who received most of the publicity from the

Evansville newspapers during this period.

News reports indicate that the Halls kept in touch with each other and shared their animals over the next few

years. When the 1897 spring season began, Col. Hall was in New Orleans and the local papers reported that

George Hall, Jr. shipped two of his camels to his father's show in Louisiana.

In May 1897, George, Jr. headed out with his wagon show. The Badger newspaper reported that his show was a

small affair, but it had some great attractions.

For a few weeks in the early summer, Col. Hall returned to Evansville and purchased "curiosities" for his show. He

was always on the lookout for the unusual and interesting. When a farmer in the area offered him a

three-headed calf, Col. Hall purchased the animal to display as one of nature's freaks.

Col. Hall returned to his show in the south, and again crossed into Mexico, this time by way of El Paso, into

Juarez. The show was combined with the Orrin Brothers circuses and traveled for six weeks to the City of Mexico,

Tampico and other Mexican cities.

In the spring of 1898, Almeron Eager received a letter from Col. Hall and Eager shared the news with the

community through the weekly Enterprise newspaper. The letter stated that Col. Hall was doing very well with his

shows and had earned nearly $17,000 in just four weeks.

When Col. Hall grew tired of the railroad show, he returned to Evansville. In September 1898, Col. George W.

Hall arrived from his two years of travel in the south. A large crowd gathered to greet the company.

Excitement and curiosity prevailed as the mammoth railroad show was unloaded at the depot. It was like a circus

parade, as the animals were taken through the city streets, back to the Hall farm at the south edge of Evansville.

George W. Hall, once again announced his retirement. "Col. Hall has come home to stay and will discontinue the

show business on account of his crippled condition and failing health", the Evansville Tribune reported.

Hall promised he would give a benefit show for the poor of Evansville, before he gave up the show business. The

benefit performance was sponsored by the Women's Relief Corp. and the show brought in $38.00 for the benefit

of the needy.

In his retirement, Col. Hall had decided to devote his time to farming. The farm was surrounded by twenty acres

of tobacco land.

Since some of his land was in the marsh, he decided to experiment with tiling. He was one of the first farmers to

install tiling to open the wetlands for cultivation. The tiles were promoted as a way to drain the marsh areas and

dry out the land.

Despite his interest in farming, Hall could not give up the circus life and he continued to purchase exotic animals.

In January 1899, a baby puma and its mother arrived. Col. Hall called the animals South American lions and

claimed that they were very docile and tame.

George W. Hall, also continued his generous donations to the people of Evansville. In 1899, the city of Evansville

began to plan for a public library. Col. George W. Hall was the first person to offer a sizeable donation. The

Badger newspaper reported his gift. "Many thanks Colonel. We hope to see the day when your gift will have a fire

proof room over its head."

When The Congregational Junior Society asked Col. Hall to provide an exhibit for a fund raiser, once again, he

kindly offered his animals for showing. An exhibit was set up in a local bicycle shop and the proceeds went to the

young people.

In addition to his farming, real estate interests in Wisconsin and Florida, and his benevolent activities, Col. Hall

was still in the business of buying and selling circus animals. In April 1899, he sold the elephant, Palm, that he

had raised from a baby. The elephant went to the Gollmar Brothers Shows, located in Baraboo. They also

purchased some of the rare tropical birds and some cages from the Hall circus.

A few days later, Hall sold more than 20 head of carriage and work horses. More of his animals and railroad cars

were sold in August 1899 to the Canton Carnival Company of Durand, Illinois.

a horizontal bar trapeze act and a tumbling act. Jessie's husband, Frank McCart, performed juggling and trapeze

acts.

Following its opening show in Evansville, the show went on the road. In June, the circus had traveled across the

prairies and reached Wyoming where a private "pleasure garden" leased the show.

That August, Col. Hall returned home to Evansville so he could begin preparing for another southern tour.

According to a Janesville Gazette report, the trip would include the Caribbean islands he had visited six year

earlier.

"Pop" Hall hired local wagon maker, Joel W. Morgan, to repair cages. Caleb Lee made new harnesses for the

horses and George Backenstoe was busy painting wagons and cages. The troupe would travel by four railroad

cars. Backenstoe was also hired to paint the railroad cars before the show turned south.

While the preparations for the southern tour were taking place, " Pop" Hall heard of a large sale of wild animals.

Always looking for new exhibits for his menagerie, Hall went to St. Louis in early August 1891 for large sale of

animals. He made several purchases and a few weeks later cages of wild animals arrived at the Evansville depot.

The purchases included two lions and a elk. He had also purchased a Brahma cow, which he billed to his circus

audiences as the sacred cow of India.

In September, the Evansville Tribune reported that "Our town is full of showmen and show fixtures preparing for

the departure of Hall's great combination shows." Hall, his son, Charles, and the Sam McFlynn Show had joined

forces for the winter.

Once again, Col. George Washington Hall displayed his generous spirit to the people of Evansville. The

Hall-McFlynn Circus gave two performances in Evansville and the proceeds from the first day were given to build

a band stand near the Central House. The second day's proceeds were given for the relief of the poor people in

Evansville.

The winter of 1891-92, the Hall shows played in Florida cities, including Tampa and Jacksonville. George Hall

sent orange blossoms and palmettos to his friends in the North. Almeron Eager, who often acted as his financial

agent, reported that the Halls had purchased more than $5,000 worth of cars, camels and show animals, and

they expected to purchase an elephant.

The combined shows were enjoying great success in Florida. Proceeds from their programs were ample to take

care of the expenses and to purchase the new equipment. "This success of Messrs. Hall is not only gratifying to

themselves, but quite as much so to their many friends at home.", a Review reporter noted in February 1892.

In the spring, the Halls returned to Evansville, to organize their shows for northern tours in the summer. All of the

children by Col. Hall's first wife were out on the road when they received word that their mother had died.

Sarah Wilder Hall had remarried following her divorce from "Pop" Hall in the 1870s. She was living in Kansas City,

Missouri at the time of her death.

Accompanied by her two daughters and their husbands, the body of Sarah H. Wilder Hall Pettengill was brought

back to Evansville for burial. The obituary notice in the September 20, 1892 Tribune told of the arrival of Sarah's

children for her funeral. Daughters Ida and Jessie were in Kansas City, Missouri with their husbands, Tod Blair

and Frank McCart.

George, Jr. was in Dubuque, Iowa and he sent his wife, Lida, to represent him at the funeral. Charles' shows

were playing in Oklahoma and he also arrived by train in time for his mother's funeral. She was buried in the

cemetery plot purchased by her son, George Jr..

Tragedy would fill the lives of Col. Hall and his children during the next few years. His daughter, Ida, had "Brights'

Disease", an inflammation of the kidneys, also called nephritis. In June 1894, Hall persuaded Ida to go to a

Chicago hospital for treatment. Her father and husband accompanied her to Chicago. Within a short while she

returned home. The newspaper announcement of her arrival noted that "she received but little help or

encouragement and is still suffering greatly from Bright's disease."

After his attempts to get treatment for Ida, "Pop" Hall returned to his show in the east. While the Hall show was in

Cincinnati, "Pop" Hall heard that a circus owned by a man named Davis was in financial trouble.

Hall contacted Davis and offered to purchase the entire show. Davis agreed and offered to include an elephant

named Empress that was leased from the Empire Printing Company of Chicago. Hall took charge of the elephant,

as well as the other circus goods.

One evening, Hall was feeding his own elephants, when Empress became jealous and attacked Hall. The animal

knocked him down with her trunk. The fall had knocked Hall unconscious and before help arrived, Empress

pressed Col. Hall into the ground, breaking his right hip. Rescuers finally arrived and took the injured man to a

hospital.

Hall was fearless and optimistic about the elephant, even if it had attacked him. He contacted the Empire Printing

Company while he was still in the hospital recovering from his injuries. The owners agreed to sell Col. Hall the

elephant for $1,000. In return, Hall promised he would not sue Empire Printing for damages. Hall's gain was a

rogue elephant that he could not tame. He sold Empress in the summer of 1895 for $2,000.

While Col. Hall was bed-ridden with the broken hip a second tragedy occurred. His daughter, Ida, died on July 9,

1894, at the age of thirty three. Her funeral was held in Evansville and because of his injuries, Hall could not

attend. Ida's brother George, was out with his show, and could also not attend the funeral.

The winter of 1894, Hall returned to Florida. The previous January he had purchased two acres of land in Tampa

and told the Tampa Times newspaper that he intended to make that his winter headquarters. The Tampa Times

reported that he intended to fence the property, build houses for his actors and stables for the horses and other

circus animals.

"Pop" Hall's circus animals arrived back in Evansville in April 1895. The animals were led from the depot to Hall's

farm. When one of the camels passed by a horse that was hitched to a post beside the street, the horse

collapsed and died of fright.

In May, two different Hall circuses once again left Evansville. Col. Hall announced that he planned to retire and

his son, Charles, would run a railroad show, while his son, George would operate a wagon show. It was the first of

several notices over the next few years, that the elder Hall would give up the show business.

George Hall, Jr. announced in April 1895 that he had purchased his father's show animals. The new show was

billed as "Geo. W. Hall Jr. Great Trained Animal Show Museum and Menagerie" and an Evansville Tribune ad

announced that the first exhibit would be in Evansville on May 4, 1895.

The younger Hall advertised that his show included his father's elephants, camels and other animals. George,

Jr.'s menagerie included the only living gorilla in America, three performing elephants, including Queen, Empress

and Palm, and 16 cages of other animals.

Hall's brother-in-law, Frank McCart performed as the slack wire walker and as an acrobat and clown. A Prof.

Showers, with his two young daughters, who were horseback riders and trapeze performers were also with the

show. When they left Evansville the show's name had changed to the Hall & Showers circus.

The following winter, in early February, 1896, Charles Hall was traveling with his circus in the southern states. He

had stopped his show in Meridian, Mississippi and was too sick with pneumonia to continue. His father was

notified by telegram that Charles was critically ill and went immediately to see him. However, Charles died before

his father arrived.